It is 6am on Friday 31st July 1987 and the temperature at the Badwater Basin in Death Valley, California, is already over 30°C. By midday it will rise to over 40°C.

British ultrarunner Eleanor Adams stands with three others waiting to start the first Badwater ultra race. Heat radiates from the ground, baking the soles of their shoes. Sweat beads on their foreheads. The four competitors, two British, two American, will cover 146 miles from Badwater, the lowest point in the US, 282 feet below sea level, to the summit of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States, 14,494 feet above sea level.

Dozens of runners have attempted the distance and a handful have completed it, but it has never been raced.

Eleanor Adams has been racing ultra-distances for five years, establishing herself as one of the world’s greatest ultrarunners, setting multiple world records. She is the outright favourite to win, but she has no experience of the dry, searing heat of Death Valley or of races at high altitude and cannot know how her body will cope. Her preparation has been no more than her normal training for multi-day events, running 140 miles a week in the temperate British climate. She has had no altitude training and her only heat acclimatisation has been spending a couple of weeks in the local area prior to the race.

How the Badwater race came about

Between 1977 and 1986, dozens of runners had attempted to complete the route from Badwater to the top of Mount Whitney and six men had succeeded. The record had been set by a New Zealander, Max Telford, in 1982. Telford completed the 146 miles in 56 hours and 33 minutes. The other runners had all taken over 70 hours. Earlier in 1987, American Linda Elam and Briton Adrian Crane had become the seventh and eight people to complete the course in a time of 69 hours and 12 minutes.

In 1986, two Californians, Tom Crawford and Mike Witwer, had tried to stage an official race along the route, but had failed to secure the necessary insurance for the runners’ support crews. They had completed the route themselves finishing in 70 hours and 27 minutes.

The 1987 race was the brainchild of the late Kenneth Crutchlow, a British entrepreneur and adventurer, and co-founder of the Ocean Rowing Society. Crutchlow had completed the route in 1973, running it in a relay with Paxton Beale. He was living in Santa Rosa, California.

The race was not an open event. Crutchlow set it up as US versus UK pairs challenge. The plan was that it would be Crawford and Witwer versus Crutchlow and another British runner. The winners would be the team with the lowest

aggregate time.

Eleanor Adams (now Eleanor Robinson) came to hear of the race through Athletics Weekly. Ken Crutchlow placed a one-page article in the 20th June edition with the title “Woman Wanted to Run Death Valley”. The article stated:

The English woman Crutchlow is looking for will have to be capable of running 146 miles, from the blistering heat of Death Valley to the frigid 14,494 foot peak of Mount Whitney. If she succeeds, she will become the first woman in history to do so and will join a select handful of runners who have completed what has come to be called ‘the longest hill’.

Crutchlow was apparently ignorant of Linda Elam’s crossing earlier that year or perhaps chose to ignore it for publicity purposes. Somewhat bizarrely his criteria included that candidates should have “at least marathon distance experience”. Given the highly demanding nature of the route, it was surely only suitable for an experienced ultrarunner. Adams commented that Crutchlow “was expecting a lot of people to take up his challenge. And of course, the only person who responded to his advert was me.”

Crutchlow paid for Adams and her two younger children, Stephen aged 12 and Joanna aged 9, to travel to the USA a couple of weeks before the event so that she would have time to acclimatise. He arranged and paid for accommodation and Adams recalls that they had an enjoyable, active holiday which included mountain biking and climbing.

Crutchlow was determined to make the race the ultimate challenge by staging it at the hottest time of the year and starting in the morning so that the competitors would run the 40 miles through Death Valley during the day when temperatures can reach up to 47°C. And then face a second day of baking temperatures at higher altitude.

Who ran the race?

Tom Crawford was the Principal of an elementary school in Santa Rosa, California. At 41, he was already a hugely experienced ultrarunner, having completed over 60 ultramarathons and he had run the Badwater ultra route the year before with Mike Witwer. He had experience of the desert conditions and high altitude that posed such a challenge for Eleanor Adams. When Mike Witwer withdrew from the challenge, leaving Tom Crawford to find another competitor, Crawford chose another Santa Rosa resident, Jean Ennis to replace him because of her mental toughness. Ennis, 41, had had childhood polio and taken up running in her thirties. Crawford and Ennis had both run the Western States 100 the month before the Badwater race. In an interview in August 1986, Crawford acknowledged that they expected Adams to win:

“We’re running against, I believe with all my heart, the greatest ultrarunner in the world. I don’t see Eleanor Adams as the greatest woman ultrarunner; she is the greatest ultrarunner…Jeannie or myself would be fools to race against Eleanor Adams. Eleanor is the epitome of the greatest athlete in the world…What we’re counting on is the fact that they have the best, and someone who’s a lot slower [Kenneth Crutchlow]…I highly respect Eleanor Adams, but I’ll tell you what: She had better not stop for tea. Because we’ll be all over her if she stops.”

Kenneth Crutchlow and Eleanor Adams made up the British team.

Crutchlow engaged David Bolling, a journalist who had written about his earlier adventures, to accompany him. The Athletics Weekly article stated that a documentary film was to be made, but there is no record that this happened.

Richard Benyo, a sports columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and former editor of Runner’s World magazine, had covered previous attempts to complete the course. He was covering the race and drove back and forth along the route so that he could report the progress of Adams and Crawford and Ennis. Benyo subsequently published a detailed account of the race in his book “The Death Valley 300”. This article draws extensively on his account as well as Eleanor Robinson’s recollections from two interviews I recorded with her in 2018 and 2019.

The race route

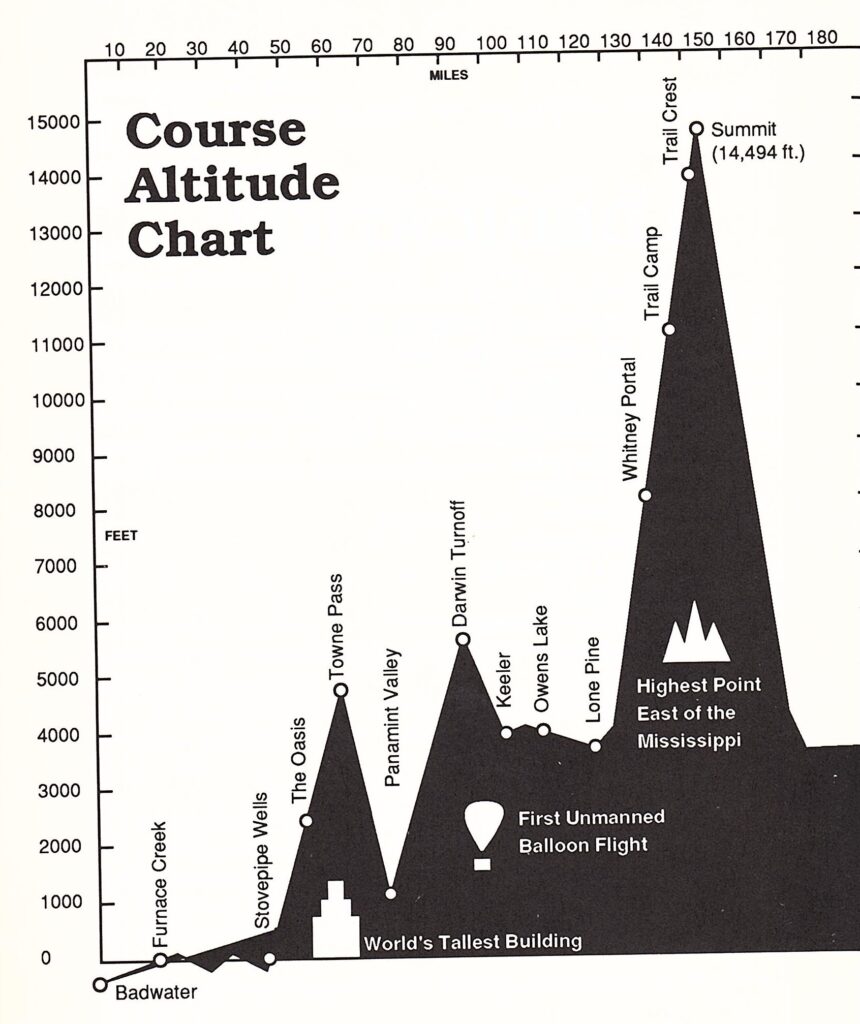

Before reading Richard Benyo’s book I had imagined that the route was a flat course through the desert until the foot of Mount Whitney. As his altitude chart makes clear this is far from the case. There are a couple of mountains to summit before reaching Mount Whitney.

Elevation chart from Richard Benyo’s Book “The Death Valley 300”

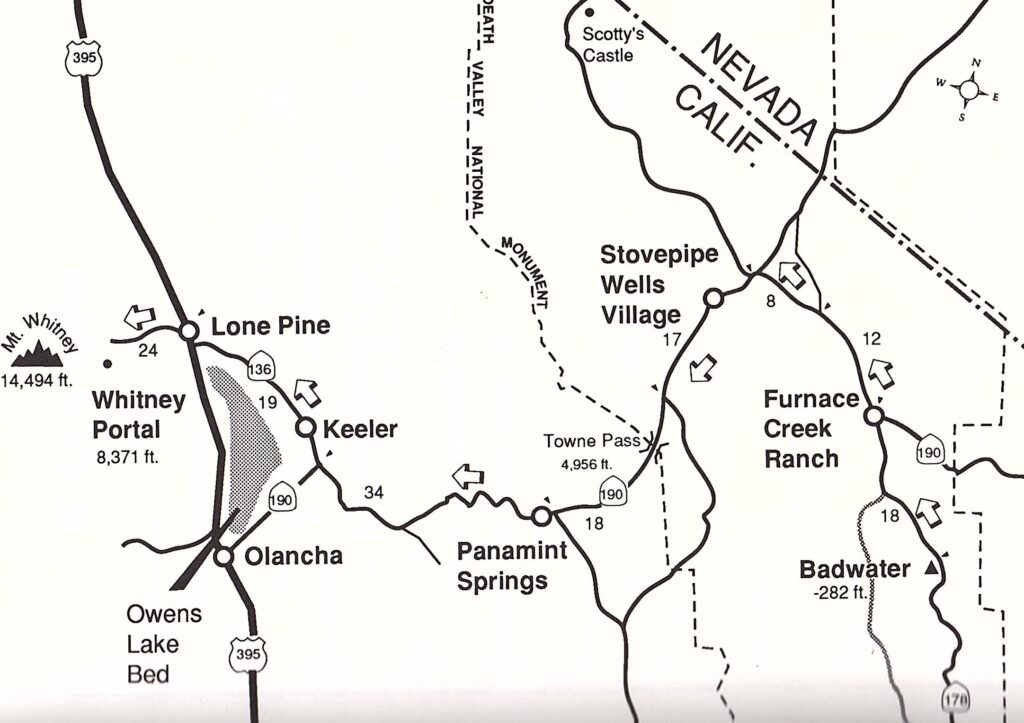

Course map from Richard Benyo’s book “The Death Valley 300”

Eleanor Adams’ experience of racing Badwater

Photo by Jakub Gorajek on Unsplash

Eleanor Adams says that races that are “quirky and difficult” and “under the worst possible conditions” have always appealed to her.

“The attraction for me was running [an end-to-end event race] from the lowest point to the highest point.”

Tom Crawford and Jeannie Ennis planned to run the race together. Adams refused to run as a pair with Ken Crutchlow:

“There was no way that I’m going to run with this guy who was definitely not a runner. He was active, but he wasn’t in really good shape. And I just said, ‘No, I’m not coming all this way to take however many days over it’. So they agreed that we’d do a cumulative time, which was fine because it meant I just went and did my own thing.”

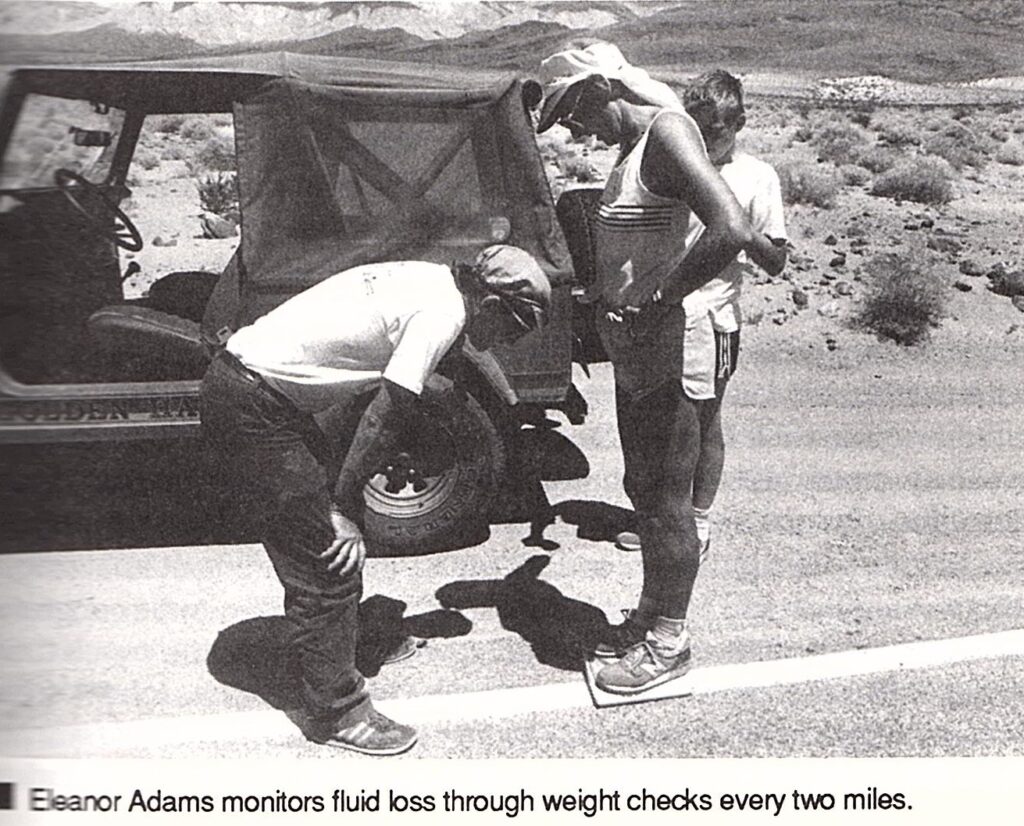

Crutchlow had arranged a support crew for Eleanor Adams. Stuart and Carol Chappell owned a motorhome rental business in Santa Rosa. They brought a 36-foot motorhome and a jeep. Carole and Joanna travelled in the motorhome and Stuart and Stephen were in the jeep which stayed close to Adams along the route. Richard Benyo relates that the British team also had a Californian doctor, Dr Daniel Weinberg, who was a specialist in endurance medicine. Dr Weinberg instructed Adams’ crew to weigh her every 2 miles so that he could monitor her fluid states to ensure she was sufficiently hydrated. At each 2 mile stop her crew also sprayed Adams all over with ice-cold water.

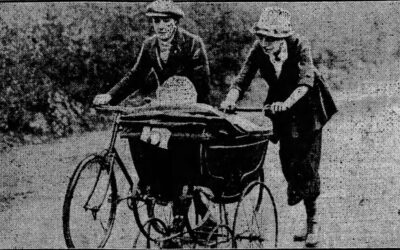

From Richard Benyo’s book – Adams’ son Stephen is standing behind her

“It was really, really tough because it was so hot. I’d no experience of running in those conditions and we were extremely exposed. Death Valley itself is only 40 odd miles long, but we set off at 6 o’clock in the morning, because you had to do it under the worst possible conditions. There was no question of running Death Valley in the night [when it would have been cooler]. We ran through the valley in the heat of the day and you could literally fry an egg. My son did it on the bonnet of the car, just to see whether it was that hot.”

A near-fatal error

Reaching the end of Death Valley at 2.13 p.m., having completed 40 miles in temperatures which had risen to 45°C, Adams had a good lead over Crawford and Ennis. Crutchlow and Bolling were many miles behind. Crutchlow had booked a motel at Stovepipe Wells at the end of the valley for both he and Adams to use for a rest. He planned to have a sleep there, but Adams knew she could only afford to make a short stop if she were to maintain her lead over the American pair.

“I made what could have been a fatal error, a really bad mistake. I went in to the motel to have a shower and a half hour rest in this air-conditioned motel room. But of course, I came out from the air conditioning into 45 degrees and I just about keeled over. And the American couple who had been a fair way behind me, in that 40-mile stretch, actually almost caught me because I really struggled. From there I was faced with this quite hard climb on the road out of Death Valley [a 17-mile stretch up to Towne Pass, elevation 4,956 ft] knowing that the American pair were not too far behind and feeling at death’s door really. It was in the nighttime by then and I just had to walk that particular stretch.”

Richard Benyo records that at The Oasis, just above the 2,000-foot point and 52 miles into the race, Crawford and Ennis were only seven and a half minutes behind Adams.

Despite this setback, Adams did not doubt her ability to continue and complete the race.

“I’d made a mistake through ignorance. There was no question of not continuing. I was there to finish and that was it. I just carried on and did the best I could. The beauty of ultra-distance running is that you can recover. You might think you’re at death’s door, but actually the body has huge reserves and as long as you’re sensible you can get over these. It’s part of multi-day running that you have these bad spells. It’s as much mental as physical. You get some really low points and as long as you’ve got the ability to continue and get through them, you do, and you then find that actually you can still compete and you can still run and you can still do it.

I wasn’t particularly concerned. I knew that I needed to keep going and I did recover, and I got back to running well.”

Completing the distance and arriving at Mount Whitney

Benyo records that the runners rested for a few, brief hours in the early hours on 1st August at a campground at Panamint Springs Lodge. Eleanor Adams setting off again at 4.30 a.m. and Jean Ennis and Tom Crawford about one and a half hours later. They were about to face a second day of unremitting exposure to the sun.

Benyo caught up with Eleanor Adams at 12.25pm when she was close to the 100-mile point.

“The temperature topped a hundred degrees [38°C]. Adams, who was slowing considerably, was looking pinched and piqued.”

Crawford and Ennis were nearly 8 miles behind and experiencing difficulties. Crawford had very bad blisters and both were suffering from the effects of dehydration. Ennis was soon to exceed the furthest distance she had ever run (100 miles). When they reached the 104-mile point at 6.22 p.m. they decided that they need to rest and left the course to travel to a motel 18 miles away at Lone Pine.

Adams continued on the course, despite being forced to slow her pace considerably and increase her rest breaks. She reached Lone Pine at 7 p.m with a lead of several hours on Crawford and Ennis. Adams was planning to sleep for a few hours before starting the journey to 13-mile journey to Whitney Portal at around midnight. Soon the runners would start the third day of the race.

At this point Richard Benyo followed the progress of Crawford and Ennis, accompanying them on foot up the mountain. As a result, he does not give a detailed account of the end of Adams’ race. Benyo did not make it to the summit as altitude sickness forced him to turn back with about 6 miles to go.

Mount Whitney by Jeremy Bishop, Unsplash

Reaching the summit of Mount Whitney

Leaving Lone Pine at around midnight, Eleanor Adams ran the thirteen miles up the zigzagging road to Whitney Portal, the last place with vehicular access. Arriving there in the early hours of Sunday 2nd August, she had to wait a while for her mountain guide, Dr Dan Weinberg to arrive. Together they hiked and scrambled the last 11 miles of the route.

At 11.10 a.m., Adams and Weinberg reached the trig point at the top of the mountain which marked the finishing point of the race. Weinberg verified her time and there were other people at the top, hillwalkers and mountaineers, who signed statements that confirmed her time of arrival. Eleanor Adams had completed the 146 miles in 52 hours 45 minutes and zero seconds, beating Max Telford’s record by over three hours.

Tom Crawford and Jeannie Ennis finished together just over six hours later in 58 hours 57 minutes and 34 seconds at 5.22 p.m. By this time, it was too late to descend and they spent a cold night in the hikers’ hut, making their way down to Whitney Portal the following morning. Tom Crawford became the first person to have completed the course twice and Jeannie Ennis became the second American woman to have completed the course and the new holder of the American’s women’s record.

Adams did not notice any effects of the altitude:

“I was dead-beat anyway, so it didn’t make much difference. It was just another thing. I just kept going. The target was a top of the mountain and that was it.”

In the final couple of miles, Crawford and Ennis were caught in hailstorms and pelted by hailstones the size of marbles and golf balls. Eleanor Adams must have been descending at this point, and according to Richard Benyo, Crawford reported seeing her coming down just before the hailstorm struck. Curiously, when I asked Adams about the hail, she could not remember it. Perhaps this was due to her exhaustion and her focus on getting back down the mountain.

What of Crutchlow and Bolling? Two and a half days after Adams had finished, they made it to the top of Mount Whitney, completing the race in 126 hours 30 minutes and zero seconds. It had taken them five days, six hours and 30 minutes.

The US team’s lower aggregate hours gave them the victory in the pairs challenge, but Adams’ achievement stands out, confirming her place in the history of ultrarunning. As far as I am aware, her time is still the fastest for an “a.m. start” (between 6 a.m. and midday) over the 146-mile course.

Badwater – the second-hardest thing I’ve done

The 1987 race paved the way for further races and in 1988 a small number of competitors undertook the 146-mile course again. At some point the race changed to become the Badwater 135 ultra which is still run today. Its slightly shorter 135-mile route stops at Whitney Portal. I believe this is because the U.S. National Parks Service did not give permission for the ascent of Mount Whitney by larger numbers of competitors but have not been able to confirm the year that this change was made. Richard Benyo lists all runners who completed the 146-mile course until 1990 in his book.

The organisers describe the Badwater 135 as “the most demanding and extreme running race offered anywhere on the planet”. It regularly features in lists of the toughest ultramarathons in the world.

For Eleanor Robinson looking back at her 16-year ultrarunning career, Badwater stands out as one of the toughest challenges and one of the things she is most proud of.

“I would certainly rate the Death Valley run as probably the second-hardest thing that I’ve done. And I made it harder for myself because I had no idea of the effects of the heat. I couldn’t prepare for it. Nowadays they’ve got heat chambers and altitude training and there’s all these things in place now to prepare people for events.”

When I asked Eleanor whether she was worried she might not complete the Badwater race, it was clear that despite experiencing some low points, she never doubted her ability to finish. This extraordinary determination is characteristic of her approach to the extreme physical challenges she has faced in her ultrarunning career….

“I never thought I wouldn’t do it, it’s there to be done.”

……………………………………….

Biographical notes:

Eleanor Robinson (formerly Adams) competed in athletics as a teenager and young woman. Her endurance running career began in 1980 when she was in her early thirties. Within two years she had competed in her first ultra distance race, a 12-hour track event at which she ran 72 miles, setting new World Records for 50km, 40 miles and 50 miles. By the time she ran Badwater in 1987, she had already competed in dozens of ultra races including 24-hour and 6-day events, setting World Records in many of them and firmly establishing her reputation as one of the world’s best ultrarunners. Later that year, she competed in the Colac 6-day Track Race in Australia, setting a new World Record of 521 miles.

When Eleanor Robinson was inducted into the International Association of Ultrarunners Hall of Fame in 2001, she chose the Badwater race as one of her top ten performances. Read about some of the other races she chose:

Westfield Sydney to Melbourne 1983

New York 6 Day Race 1984

Colac 6 Day Race 1984

Melbourne 24 Hour Track Race 1989

IAU International 24 Hour Championships Milton Keynes 1990

IAU 100km World Championships 1990 & 1991

Telecom Tasmania Run 1994

Nanango 1000 Mile Track Race 1998

and another race that did not make it into the top ten:

1983 The first Spartathlon

Sources for this interview:

I interviewed Eleanor Robinson (formerly Adams) in June 2018 and May 2019.

With thanks to Richard Benyo for allowing me to reproduce images from his book:

The Death Valley 300, Richard Benyo, Specific Publications Inc, 1991

The Death Valley Challenge: An Interview with Tom Crawford and Jeannie Ennis, originally published in Northern California Sport, August 1986

“Death Valley to Mount Witney”, Eleanor Robinson, Australian Ultrarunners Association newsletter, May 1988

The Badwater 135 website and “1987 – The Year Badwater Became a Race”, an article by Chris Kostmann (Director of the Badwater events) originally published in Runner’s World Magazine in August 1988.

0 Comments