When Eleanor Adams (now Robinson) took part in the first Spartathlon, a 245km race from Athens to Sparta, in September 1983, she was relatively new to ultrarunning. She had run her first ultramarathon, a 12 hour track race, in July the previous year. She had competed in a 100km track race (in which she covered 54km) and three 24 hour races. Adams had already established herself as one of the world’s best female ultrarunners, setting world bests for 30 miles, 50km and 40 miles. Just two months before the Spartathlon, she competed in the Charles Rowell 6 Day Track Race in Nottingham, setting a 6 day world best of 659.298km. This was to be the first of many world bests for 6 days (including New York and Colac, Australia).

Entering the Spartathlon

Adams was 35 when she ran the Spartathlon. It was only her second invitation to an international race. In April 1983, she had been invited to compete in a 24 hour race in Vienna, where she had finished first woman with 188.784km. Adams planned to attend the race with fellow members of Sutton-in-Ashfield Harriers & Athletics Club, Alan Fairbrother and George Slack. They had raced together in the 12 hour race in 1982.

However, entering the race proved not to be straightforward for Adams as she explained in the Legends of Spartathlon podcast in September 2020:

The difficulty I had in being accepted into the race [was] because the whole ethos of this race was based on a military event. The organisers were very much against having a female competitor and it was only due to the intervention of the male ultrarunners that I was allowed to compete. So I didn’t know until the very last minute that I was going to be going to Greece so I did no specific preparation for this event.

Adams was the only woman in the race. Her husband, John, travelled with her to Greece and during the race he got lifts so that he could see Adams at various points along the route.

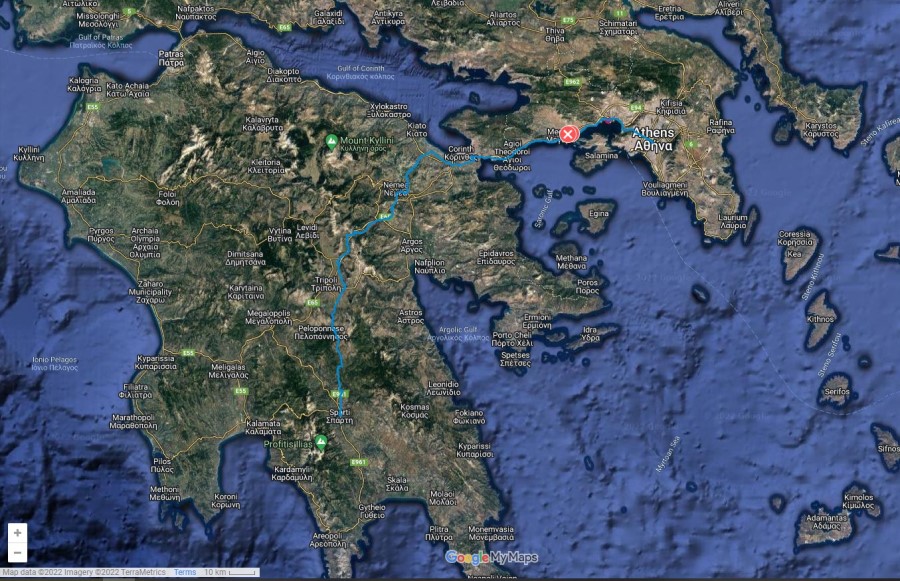

The route map from the official race website, spartathlon.gr

The origins of the first Spartathlon in 1983

An article about the inaugural Spartathlon appeared in the Road Runners Club newsletter in April 1984. It featured reports on the race from Alan Fairbrother and Eleanor Adams. The introduction and Adams’ account of the race are reproduced below with the kind permission of the Road Runners Club.

The Pheidippides Legend – Athens to Sparta

RAF Wing Commander John Foden, veteran distance runner and a student of history in his youth, became interested in the legendary account of how the professional courier Pheidippides ran from Athens to Sparta (250km, 155m) in two days, to seek help from the Spartans, for the Athenians against the giant Persian army who, in BC490, had landed on the plain of Marathon.

Having failed to gain support from the King of Sparta, Pheidippides ran back to Athens, continuing to Marathon where he fought in the battle in which the Greeks, overwhelmed in numbers, defeated the gigantic Persian army in one of the decisive battles in world history.

The rest of the story is well known to marathon runners since it is the origin of the modern marathon race. Pheidippides threw down his arms after the battle and ran back to Athens with the joyful news of the Greek victory, collapsed and died.

John Foden spent five years researching the history of that era in consultation with Professor N. Hammond of Clare College, Cambridge, a classical historian, who had acquired first-hand knowledge of the mountain routes between Athens and Sparta as liaison officer with the partisans during the Second World War.

The RAF 1982 Expedition

After a preliminary expedition in 1980, John Foden organised another in 1982, comprising eleven experienced RAF long distance runners, to investigate the route which Pheidippides might have taken to Sparta nearly 2500 years ago and also to find out if the journey could be completed in two days. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing fifty years later, said Pheidippides had arrived in Sparta the day after he had left Athens.

The team of eleven, of whom six were likely to run, with the remainder driving support vehicles, had to make a long and tiring journey overland to Greece. The time was limited, and so were their funds. It had been realised that personal contributions could not cover the entire cost, although support had been received from the Trenchard Memorial Award fund, CILOR and an RAF Expedition grant. In fact when they arrived in Athens it looked as though they might have to make tracks for home straight away.

However, it was here that Mike Callaghan appeared, and obtained support from a number of British business firms in Athens. He acted as co-ordinator with the RAF team, and saw the opportunity of establishing a race between Athens and Sparta in conjunction with SEGAS, the Greek athletic organisation.

Three of the RAF 1982 expedition completed the journey, held at the same time of year as Pheidippides run in between 34.5 and 39 hours, i.e. within two days, but no definite conclusion could be reached as to the exact route which Pheidippides might have followed through the mountains.

Eleanor Adams’ account of the first Spartathlon

The race named the “Spartathlon” was held on 30th September to 1st October 1983. It had a 36 hour completion time limit and four checkpoints with cutoff times. This is Eleanor Adams’ account of her race, written not long after it took place.

“I had a very good run in Greece and thoroughly enjoyed it.

“It was a great thrill to be invited, but I must admit to much trepidation, with many of the world’s best ultrarunners, the heat, the terrain, not to mention the strict time limits.

The days before the race

“It was somewhat disturbing to find ourselves lost at least six times on the coach trip of the course. This did little to promote athletes’ confidence that they would be able to find the correct route if the organisers were unsure of the way.

“We were able to view the notorious mountain section, the top of which seemed to be a scramble up what appeared to be a sheer incline. The thought of tackling this in the black of night was terrifying. We had been unable to see the other side, which was reputed to be even worse.

“The rest of our time before the race seemed to be spent travelling on a coach from reception to reception. We had little time for training; hardly any time in the sun; and not even any regular meals. Consequently the evening prior to the race saw most of the athletes very frustrated and very weary, not exactly the ideal preparation for any race, let alone one of this magnitude.

“I was rather concerned about the haphazard organisation along the course. It was with a great deal of trepidation that I found myself on the start line after a sleepless night. I was the only lady taking part, and under tremendous pressure to do well. I had been subjected to a barrage of press and well-wishers all week.

Race day

“The race took place during two very hot days; it was frustrating to find the next two days to be quite cool.

“I set off a reasonable pace as I was anxious to give myself plenty of time in hand for the mountain section. I knew there was no way I could run over the mountain (I couldn’t have done that anyway, let alone after 100 miles!). I thought the time limits for each section were quite unfair. I wanted to give myself as much time as possible to tackle that section, so I arrived a Corinth (51 mile) in 7h 2m.

“My first problems arose as darkness was falling. My torch and reflective band were not at the appropriate check point. Immediately this wasn’t too much of a problem as I was on a good path, but I knew it wouldn’t be long before I would be on very rough tracks. Eventually another torch was brought to me. Several other athletes had similar problems; unable to locate shoes, clothes, etc., sent to various checkpoints.

“I found it impossible to run on the rough tracks, a sprained ankle or twisted knee would have put me out of the race, so I settled for a fast walk. I came to the mountain section at 1 a.m. I was fortunate to have the company of Gerard Stenger. We both decided that perhaps it was as well it was dark, making it impossible to see the huge drop below us!

“Much to my relief I cleared the third crucial section with hours to spare. I knew then that I would finish, it was only a matter of time. By the time I reached the fourth elimination point, I was feeling decidedly weary and rather weak. The previous evening I had been violently ill and unable to keep down anything solid, next day I was unable to keep down any liquids, and I was fearful of becoming dehydrated. Because of this, I took the last section very easily, and the last eighteen miles, although downhill, seemed endless.

“The Greek people had really taken this race to their hearts and were out cheering us even in the middle of the night. Towards Sparta, the people were even more enthusiastic, offering me food and drink, pressing flowers into my hands. What a magnificent finale, and how tremendous to mount the steps and touch the statue of King Leonides. All I wanted to do then was to have a bath and a good sleep.

“I’ve tried to convey that the race was tremendous, and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Nevertheless many aspects of the organisation left a lot to be desired. I had the feeling that the organisation was more interested in the commercial aspects of the event than in the well-being of the athletes.

“There were other marvellous people though who were willing to help in any way.

“I personally hope that the organisers won’t be tempted to make this an annual event, but rather have it every two or four years to keep it as an “extra special event”.”

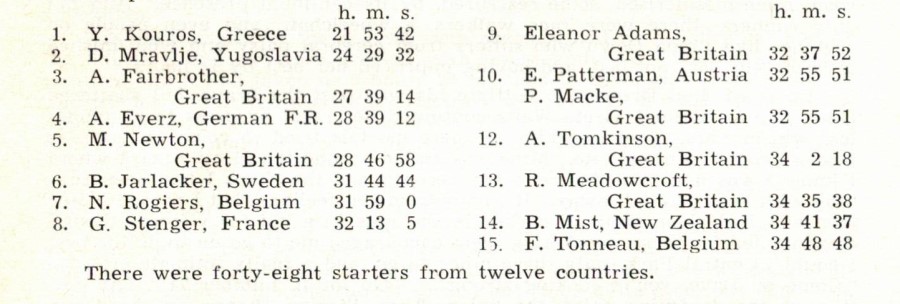

Spartathlon 1983 results

These results are from the Road Runners Club newsletter. The DUV website lists another finisher within the 36 hour cutoff, Takis Skoulis of Greece. However, Patrick Macke, who finished tenth, has clarified that Skoulis did not complete the race as he was timed out at the Nestani checkpoint. The documentary states that there were 44 starters. Most runners probably had to withdraw from the race because they didn’t meet the cutoff times.

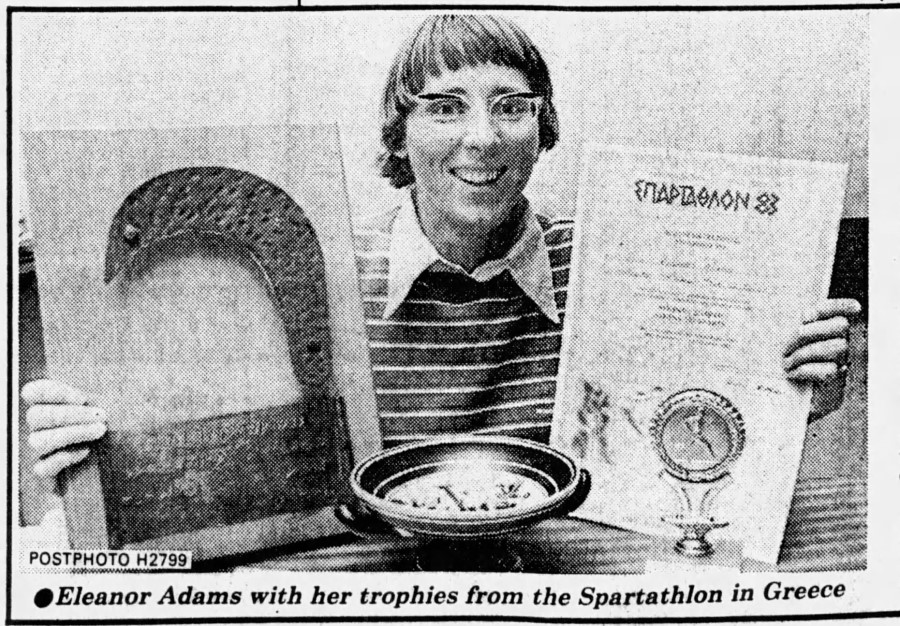

Eleanor Adams was the first and only woman to finish the first Spartathlon. She finished ninth overall. When I interviewed Eleanor in 2018, she described how supportive the male runners had been when the organisers didn’t want to admit her “even though most of them were getting beaten by a woman“. She was leading the way for the many hundreds of women who have competed in the race in its forty year history.

I was always very conscious of being a pioneer and that was one of the motivating factors for me. I was well aware of the fact that there were very few women [doing ultrarunning] and that I was fortunate in that I was around at the right time and able to take the opportunities. I was doing it not just for me but for other women that might want to. I knew it wasn’t the sort of thing that would attract hordes of people, but it would make the way easier for anybody else that wanted to come along and do similar things.

Her Sutton-in-Ashfield team mate, Alan Fairbrother, finished third. This placing is remarkable given that he had run in the Road Runners Club London to Brighton ultramarathon (53 miles) just five days before.

The third club member, George Slack, was eliminated after missing a cut-off at a checkpoint by 15 minutes.

Adams did not return to the Spartathlon but Fairbrother did, running it four more times in 1984, 1985, 1987 and 1992, when he was 56.

Nottingham Evening Post, 5th October 1983, newspapers.com

Notes

The organisers of the Spartathlon have said that 2022 marks the fortieth running of the race, however there was no race in 2020 due to the Covid pandemic and therefore it might more accurately be described as the 39th Spartathlon (unless they are counting the 1982 RAF expedition as the first race). There were 388 runners on the start list this year.

The British Spartathlon team website features a photo of the 1982 team with John Foden centre. Foden, the originator of the race, was a member of the Road Runners Club and also of my running club, Holme Pierrepont Running Club, Nottinghamshire, which was founded in 1982. The Road Runners Club was founded in 1952 to promote distance running for men in the UK. It had members across the country and played a significant role in the development of road racing up to the marathon distance, as well as road and track ultramarathons. It still exists today.

Eleanor Adams’ club in 1983, Sutton-in-Ashfield Harriers & Athletics Club, is the oldest Nottinghamshire athletics club to still exist under the same name. Its club crest show a foundation date of 1908. (More about Nottinghamshire athletics clubs.)

There is a grainy copy of a 1983 documentary about the race on Youtube. In the film some of the runners talking about what the race means to them. It shows the start of the race at the 1896 Olympic stadium in Athens and the runners weaving through heavy traffic. Alan Fairbrother gets quite a lot of coverage as he was in third place for most of the race. Eleanor Adams is shown finishing the race towards the end of the film.

Davy Crockett has written two articles about the origins of the Spartathlon and the first race on his Ultrarunning History website.

The banner photograph is a view of the monument to the hero of Sparta, Leonidas, in the modern town of Sparta, Laconia, Peloponnese (Greece) by Jean Housen. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Interview with Eleanor Robinson, June 2018.

Some more of Eleanor’s races:

1984 New York 6 Day Race

1984 Colac 6 Day Race

1986 Westfield Sydney to Melbourne Race

1987 The first Badwater Race

1989 Melbourne 24 Hour track race

1990 IAU International 24 Hour Championships Milton Keynes

1990 & 1991 IAU 100km World Championships

1994 Telecom Tasmania Run

1998 Nanango 1000 Miles track race

Takis Skoulis did not finish the 1983 Sparathlon. He did not reach the Nestani checkpoint within the 24 hr time limit and eventually travelled by car to Sparta. (In the same car as Michael Callaghan the race organiser!!)

Thank you very much for commenting Patrick and for clarifying that Takis Skoulis didn’t finish. It did seem strange that he wasn’t listed in the RRC results. It is particularly nice to hear form you, as you competed in several races with Eleanor. You are mentioned in at least two other posts on my blog: the Westfield Sydney to Melbourne race and the 1989 Melbourne 24 Hour track race.

Katie