At 10.30 am on 27th April 1983, the New South Wales Premier fired the starter’s gun on a race that was to make a national hero of its winner and create one of the most famous Australian ultramarathons, the Westfield Sydney to Melbourne race.

Eleven men lined up in the carpark of the Westfield shopping centre in Parramatta, a suburb of Sydney. By the time Cliff Young, a 61-year-old potato farmer from Colac, Victoria, reached the Doncaster shopping centre in Melbourne 5 days 15 hours and 4 minutes and 864 km later, the race had attracted huge attention in Australia and people from other countries were enquiring about how they could enter it. The favourite to win the race was Siegfried (Siggy) Bauer from New Zealand. Young’s victory was a surprise to everyone, not least himself.

The Sydney to Melbourne race took place every year until 1991. After that Westfield withdrew their sponsorship and the race could not continue without it.

1984 – the first female competitor in the Sydney to Melbourne race

In 1984, there were 31 starters including a woman, Australian Caroline Vaughan. Vaughan was not amongst the nine finishers.

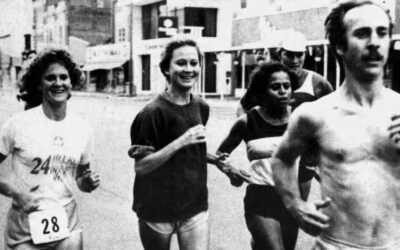

1985 – Eleanor Adams enters the race

In 1985, Eleanor Adams competed in the Sydney to Melbourne race for the first time. 27 competitors started the race, including three women, Adams, Donna Hudson from the USA and Margaret Smith from Melbourne. Eleanor Adams had set a new world best for 6 days at the inaugural Colac race in November 1984 and was the favourite to win this race too.

Eleven runners finished the 960km route: eight men and all three women with Adams finishing in seventh place in 8 days and 30 minutes, 11 hours ahead of Hudson who was eighth and Smith coming in ninth place another 5 hours later.

1986 – Eleanor Adams’ best performance in the Sydney to Melbourne race

Eleanor Adams returned as the favourite in 1986. Phil Essam reports in his book about the Westfield races that the women’s prize was 10,000 Australian dollars, the biggest women’s prize ever for an ultramarathon. Second prize was 5,000 dollars. However, prize winners were likely to find that the cash only covered their participation expenses, which included the costs of their support teams and vehicles.

There were 28 starters, including four women: Adams and Donna Hudson who had both returned after 1985, Australian Cynthia Cameron and British runner Christine Barrett. Barrett had been invited at the last minute after US runner Marcy Schwam withdrew.

Promotional picture of Donna Hudson, Eleanor Adams and Christine Barrett dining out at an Italian restaurant on 30th April

The 1986 route was 1005km. The race started on 2nd May. Of the 28 competitors, only nine completed the race: six men and three women. Cynthia Cameron had been forced to withdraw on Day 4 due to a knee injury but would return the following year and take the top women’s spot.

Phil Essam records comments made by Eleanor Adams to the press before the race.

Eleanor Adams, who was first woman home last year said that there were so many unknown factors in the race that it was impossible to make predictions. “There’s no way you can confidently say you’ll even finish.”

“All the time you say to yourself, why am I doing this? Around four in the morning, just before dawn is the worst time. The body is at its lowest level. And you know the pain is not going away for the rest of the race.”

Eleanor Adams steadily moved up the rankings in the course of the race, and by Day 5 she was in fourth place. She maintained this placing until she finished the race on Day 8. In the nine-year history of the race Adams was the highest ranked female finisher and the only woman to complete the race three times, winning each time.

The finishing time (days: hours: minutes) were:

-

- Dusan Mravlje 6:12:38

- Brian Bloomer 7:04:53

- Patrick Macke 7:13:02

- Eleanor Adams 7:17:58

- Joe Record 8:01:14

- Donna Hudson 8:06:15

- Bertil Jarlacker 8:15:13

- Ross Packer 8:17:45

- Christine Barrett 8:22:30

Eleanor Adams’s account of the 1986 Sydney to Melbourne race

When she was inducted into the International Association of Ultrarunners Hall of Fame in 2001, Eleanor Robinson (formerly Adams) was asked to choose the top ten performances of her career. The 1986 Sydney to Melbourne race was number seven on her list. This is her account of the race from the IAU Newsletter, March 2001.“I ran in three Sydney to Melbourne races, 1985, 1986 and 1988, finishing first lady each time. As with the Colac Six Day Races I tend to remember them as a group but have picked out the 1986 race as it was my best performance. The Sydney to Melbourne was a unique event, not simply because it was a point to point and could not therefore duplicated anywhere else but because it was more than just a race. It was a spectacle, a huge media event, which stirred the imaginations of all Aussies and created mass interest and involvement. Suffice to say that I had never seen anything like it before or since. The race organisers quite openly claimed that if they could have had the race without the runners they would have done so.

“We were subjected to intense media attention from the moment we arrived in Australia and attended press conferences, football matches, presentations and gave radio interviews at unearthly times, in fact anything at all that would gain publicity. The hype grew more and more intense as race day approached.

“Each runner was assigned a crew of 6 and 2 camper vans. Once on the road we were to be completely self-sufficient. Having run in 1985 I knew what to expect and, on this occasion, I was able to put together my own crew from friends I had made on my frequent trips over. My son, Stephen, who was then just 12 years old also came along to help. A good crew is an enormous help but events in this race made me wish I was on my own as was more the norm.

“Of all the races I have taken part in the Sydney to Melbourne has to be the most dangerous of them all. The route between these two major cities was not along quiet country lanes but instead straight down the Hume Highway, the major traffic route and equivalent of our motorway and not dual or divided in places either. The runners had the hard shoulder, a very narrow strip at the edge of the road, but our support vehicles, being much wider and following behind slowly, were always in with the rest of the traffic. The vehicles were well signed and lit, and all involved wore the sponsor Westfield’s kit so that we could easily be recognised. Publicity was enormous so that there should have been no doubt what, and who, we were. However, all the events that I know of can relate some dangerous incident and 1986 was no exception.

“Only two days into the race and the lead runner, Geoff Kirkman from Adelaide, was seriously hurt. Approaching the brow of a hill, a car decided to overtake his support vehicle and moved into the middle of the road. A semi-trailer coming up the hill from the other side was also in the middle lane. They hit each other at the top. Luckily, Geoff was still running up but was hit by flying debris as was his support van. He was seriously injured and in hospital for a long time, never to run again. His van was smashed and his crew suffered minor injuries. [The driver of the car was killed on the spot.] The race management met each approaching runner and guided us around the debris.

“It was a sobering moment and with plenty of time to reflect I came to the conclusion that, no matter how challenging the event, the risks were unacceptable. I had always realized that I was very vulnerable but now as the horror of the situation hit home, I felt totally responsible for my crew. After all, I was the reason they were there, and I would have to live with that knowledge should anything happen to one of them. Responsibility for their safety weighed very heavily upon me.

“The whole situation was made even worse by the attitude of the “truckies”. Speed restrictions on the Hume Highway were lifted a night-time so making it essential for the drivers to get between the two cities at night. Not only would all the trucks roar past at high speeds but it was a favourite game among some of the drivers to see how close they could get, particularly to the “sheilas”. The effect of the down draught from a semi-trailer was to blow you off the road into the metal barrier. Not pleasant! The truckies would use the CB radio to identify the Westfield competitors and pass information to each other.

“This particular brand of Aussie humour I did not appreciate, and it was one aspect of the Aussie lifestyle that I never liked. Nevertheless, I had a race to run and I tried to concentrate on that. I ran much faster than the previous year over a longer course though had to walk the final stretch to Melbourne due to a knee injury.

“Multi-day running is a fine balance of striving to get the most out of your body without exceeding its limits and thus getting injured. I took fourth place overall and was first lady. I was overjoyed to do so well and relieved that I had got myself and my crew to the finish line safely.

“I refused to return until a safer route was used and so missed the 1987 race. In 1988 the Princes Highway was used instead and though still busy this was much better alternative. I ran my fastest time on this longer route in 1988 and finished running strongly. Some might say a better performance but given the trauma of 1986 I have selected that race.”

Back for a third victory in 1988

The 1988 route along the Princes Highway was 1016km. Due to the popularity of the race, the organisers introduced a qualifying standard for the time. Runners had to have completed, or got close to, 200km in a 24-hour race. There was also a cut-off time of 204 hours (8 days and 12 hours).

1988 was Australia’s bicentennial year and the race was awarded the status of being an official bicentennial event.

The race started on 17th March. Three women competed: Adams who was now 40, Sandra Barwick of New Zealand and Mary Hanudel of the USA, who had finished second two hours behind Cynthia Cameron the previous year. Twenty-two runners completed the race before the cut-off time. Eleanor Adams finished in 10th place in 7 days, 10 hours and 5 minutes, crossing the line with fellow British runner Patrick Macke at 8.05pm on Day 8. Sandra Barwick finished 17th in 8 days, 4 hours and 10 minutes. Mary Hanudel had been injured in an accident on Day 7 when her support vehicle ran into her. She withdrew from the race and required ankle surgery.

Women who completed Sydney to Melbourne

Over the nine years that the race was run, there were 124 finishes by 61 male athletes and 7 female athletes from ten different countries. The female finishers were Eleanor Adams (three times), Donna Hudson and Sandra Barwick (twice), Margaret Smith, Christine Barrett, Cynthia Cameron and Mary Hanudel.

It is noteworthy that in 1985, of the 24 male runners only eight finished whereas all three women finished. And again in 1986, of 24 men only six finished whereas three of the four women finished. Over the nine years the event was

held, of the 13 women who started the race seven completed it.

It would be interesting to find out the reasons for the much higher rate of completion of the female runners than the male runners. Were male runners more likely to overestimate their abilities when entering extreme endurance events? Were the women of a higher calibre as ultrarunners? Or were the women better at coping with pain over a long period?

Perhaps the women had something to prove both to themselves and to society. From her first ultra race in 1982, where she set new world best times for 50km, 40 miles and 50 miles, Eleanor Adams set dozens of ultrarunning world bests and UK bests in the 1980s, often breaking her own records. Part of her motivation was opening the way for other women to compete.

I was always very conscious of being of a pioneer and leading the way and opening it up for other women to have the opportunities and that was one of the motivating factors for me. I was well aware that there were very few women competing and that I was fortunate to be around at the right time and able to take the opportunities. I was doing it not just for me but for other women that might want to.

Notes

My descriptions of the races draw extensively on Phil Essam’s book: I’ve Finally Found My Hero – The story of the Sydney to Melbourne Ultra Marathons (1983 to 1991), self-published, 1999.

Results of all the events and of many other ultra races over the years can be found on the Deutsche Ultramarathon Vereinigung website.

There are many videos on Youtube about the race, particularly about Cliff Young and the inaugural event in 1983. I have not found any coverage of the years in which Eleanor Adams competed.

Read about some of Eleanor Adams’ other top ten performances:

1984 New York 6 Day Race

1984 Colac 6 Day Race

1987 The first Badwater Race

1989 Melbourne 24 Hour Track Race

1990 IAU International 24 Hour Championships Milton Keynes

1990 & 1991 IAU 100km World Championships

1994 Telecom Tasmania Run

1998 Nanango 1000 Miles track race

and another race that did not make it into the top ten:

1983 The first Spartathlon

Women’s superior endurance in long distance ultras – A study published by RunRepeat.com and the IAU in February 2020 found that female ultra runners are faster than male ultra runners at distances over 195 miles. The study analysed the results of over 15,000 races held between 1996 and 2018. The longer the distance the shorter the gender pace gap. In 5Ks men run 17.9% faster than women, at marathon distance the difference is just 11.1%, 100-mile races see the difference shrink to just 0.25%, and above 195 miles, women are actually 0.6% faster than men.

0 Comments