Women’s participation in road running in the UK has grown considerably in the past 15 years and it is not uncommon for women to make up over 40% of finishers in road races. Yet in ultrarunning, women’s participation is much lower, perhaps around 30%, but this varies significantly from race to race. I “dot watched” the Montane Spine Race this year, a challenging 268-mile 7-day ultramarathon along the route of the Pennine Way. Women accounted for just 17% of the competitors. It was this that prompted me to ask, how has women’s participation in ultrarunning changed over the past 50 years?

In 1973, women’s long-distance running was only just beginning. Did women’s participation increase steadily from a very low base in 1973 or have there been periods of sudden growth or even of decline?

Tracking women’s participation in ultras over 50 years

I decided to track participation in five high-profile international ultramarathons at ten-year intervals from 1973 to 2022/23.

The races that I selected were:

- Comrades Marathon, South Africa

- London to Brighton, UK

- 100km del Passatore, Italy

- Spartathlon, Greece

- Western States Endurance Run, USA

There are not many ultramarathons still going today that have been held for 50 years. Indeed, only two of my selected races have been held since 1973, Comrades Marathon which started in 1921, and 100km Del Passatore which started in 1973.

To find the data I referred to results published on race websites, the newsletters published by the Road Runners Club and International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) and the DUV website.

Other data on women’s participation in ultrarunning

In 2019, I analysed the results of 12 UK ultras that had taken place in 2018/19. They varied in distance from 30 to 100 miles. I found that 30% of the 3,531 finishers in these races were women. However, there was a wide variance across the twelve races – 16% was the lowest percentage of female participants and 37% the highest.

In 2020, Runrepeat and the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU) issued a joint report, The State of Ultrarunning 2020, which included an analysis of results from over 15,000 ultra races over 23 years (1996 to 2018). It found that there was huge increase in participation in ultramarathons over the period whereas participation in marathons had levelled off. The authors concluded that “the most dedicated runners are looking for bigger and bigger challenges”. The report also commented on the participation of women:

There have never been more women in ultrarunning. 23% of participants are female, compared to just 14% 23 years ago.

This participation rate is lower than the figure I found in my small UK sample. However, the report gives female participation figures by country and the figure for the UK was 27% which is closer to the figure I found.

Women and long-distance in the 1970s

For most of the twentieth century, long-distance running was reserved for men. At the start of the 1970s, 1500m was the longest women’s track distance recognised by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF). International cross country races were no more than 4 miles. There was no international road race competition for women and women were banned from most long-distance road races, including the marathon. Eventually the governing bodies of athletics changed their rules, following rule-breaking and campaigning by women who saw no good reason for their exclusion.

In this context, it is not surprising that few women competed in ultramarathons in the 1970s. Women were new entrants to the sport of distance running and were unlikely to start by running ultramarathons. Also, some race organisers were slow to admit women to what they saw as men’s races. But there were women who challenged the status quo and that happened in two of the races in my list.

Only one of the five races admitted women in 1973, the 100km Del Passatore. 4% of the finishers were women that year.

Comrades Marathon, South Africa

First year held: 1921

First year women officially admitted: 1975

Distance: 87km-90km

Route: the race takes place between the cities of Durban and Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal province. The direction of the race alternates each year between the “up” run (87 km) starting from Durban and the “down” run (90km) starting from Pietermaritzburg.

Comrades is the world’s largest and oldest ultramarathon race, with thousands of finishers. In 1975, the race organisers officially admitted women and people of colour for the first time.

But women had raced unofficially before then. In 1965, the organisers permitted Mavis Hutchison to participate in the race. She ran Comrades unofficially four more times before the ban was lifted. In 1966, she was the only woman to finish and in 1971, 1972 and 1973, she was joined by Betty Cavanagh.

1973 – women not permitted to run, Mavis Hutchison and Betty Cavanagh raced unofficially.

race date

31st may 1983

31st may 1993

16th june 2003

2nd june 2013

28th august 2022

finishers

5,364

11,320

11,416

10,816

11,713

number of women

159

1,102

1,871

1,956

2,380

female finisher %

3%

10%

16%

19%

20%

London to Brighton

First year held: 1951. The last road race was held in 2005.

First year women officially admitted: 1980

Distance: around 53 miles

Route: From Big Ben in Westminster, London to the Aquarium in Brighton

London to Brighton started in 1951, the year of the Festival of Britain (see Road Running in the UK in the 1950s) . It was organised by the Road Runners Club (RRC) from 1952 until growing difficulties with traffic forced it to stop in 2005. Despite this, London to Brighton still stands as the longest run ultramarathon in the UK. The race started to build a reputation and from 1953 it attracted runners from other countries. There was a long-lasting link with the Comrades Marathon.

1973 – Women were not permitted to run. (They were not even permitted to join the Road Runners Club as full members until 1976.) However, Scottish runner Dale Greig had run the race unofficially in 1972.

By 1979, the Road Runners Club still hadn’t allowed women to enter their flagship race. Five women decided to enter London to Brighton unofficially. Two of the women dropped out but the other three all finished well within the 8 hour 23 minute time limit. Leslie Watson finished first in 6 hours 55 minutes and 11 seconds, faster than most of the men. The next year, the RRC officially accepted women competitors for the first time with a trophy for the female winner.

The 1993 figures include finishers who were outside the 9.5 hours cut-off. Carolyn Hunter-Rowe and Hilary Walker finished within the cut-off and two other women (and one man) finished outside it.

race date

25th september 1983

3rd october 1993

5th october 2003

finishers

154

82

87

number of women

3

4

12

female finisher %

2%

5%

14%

100km Del Passatore, Italy

First year held: 1973

First year women officially admitted: 1973

Distance: 100 km

Route: The course starts in Florence, winds its way up over the Apennines, and down to the finish in Faenza

Although dwarfed by the Comrades Marathon field, this race has always been a mass participation event with over 800 finishers most years. There was a peak of 2,674 finishers in 2019.

This is the only one of the five races that permitted women competitors in 1973. The race may have been part of a long-distance walking movement rather than an athletics event. If this was the case, it would have meant that the race did not come under the jurisdiction of the Italian national governing body of athletics1. 4% of the 337 finishers in the inaugural race in 1973 were women – 15 women finished.

On 25th May 1991, the fifth IAU 100km Championships were held at the 19th 100km Del Passatore race. Eleanor Robinson won the race.

race date

28th may 1983

29th may 1993

24th may 2003

25th may 2013

21st may 2022

finishers

1,301

907

907

1,452

2,441

number of women

59

51

86

178

478

female finisher %

5%

6%

9%

12%

20%

Spartathlon

First year held: 1983

First year women officially admitted: 1983

Distance: 250 km

Route: Athens to Sparta – road and trail

In 1982, Royal Air Force Wing Commander John Foden, a veteran distance runner, got a small team of RAF men together to attempt to re-create Pheidippides’ legendary run from Athens to Sparta in BCE490. The following year, the race was born and a number of men were invited to take part. Foden was keen for the Spartathlon to be an entirely male endeavour, but Eleanor Adams (now Robinson) was able to persuade him to admit her as the sole female competitor.

The Spartathlon attracts a wide international field each year. In 2022, runners from 37 countries took part. And winners in recent years have come from Greece, Latvia, Japan, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, USA, Germany and Italy.

race date

20th september 1983

24th september 1993

26th september 2003

27th september 2013

30th september 2022

finishers

16

49

84

148

182

number of women

1

5

6

14

34

female finisher %

6%

10%

7%

9%

19%

Western States Endurance Run

First year held: 1977

First year women officially admitted: 1978

Distance: 100 miles

Route: The race is along the middle portion of the Western States Trail. It starts at Olympic Valley, California, and ends in Auburn, California. The route is remote and rugged with many thousands of feet of ascent and descent.

The Western States Endurance Run describes itself as the world’s oldest 100 mile trail run2. It traces its start back to 1974, although there was only one finisher for the first three years. Hence I have given 1977 as the start year.

There are small discrepancies between the number of female finishers listed on race website and on DUV. I have used the figures from the race website.

race date

25th june 1983

26th june 1993

28th june 2003

29th june 2013

25th june 2022

finishers

196

209

272

277

305

number of women

21

35

55

52

69

female finisher %

11%

17%

20%

19%

23%

Thoughts on women’s participation in ultrarunning

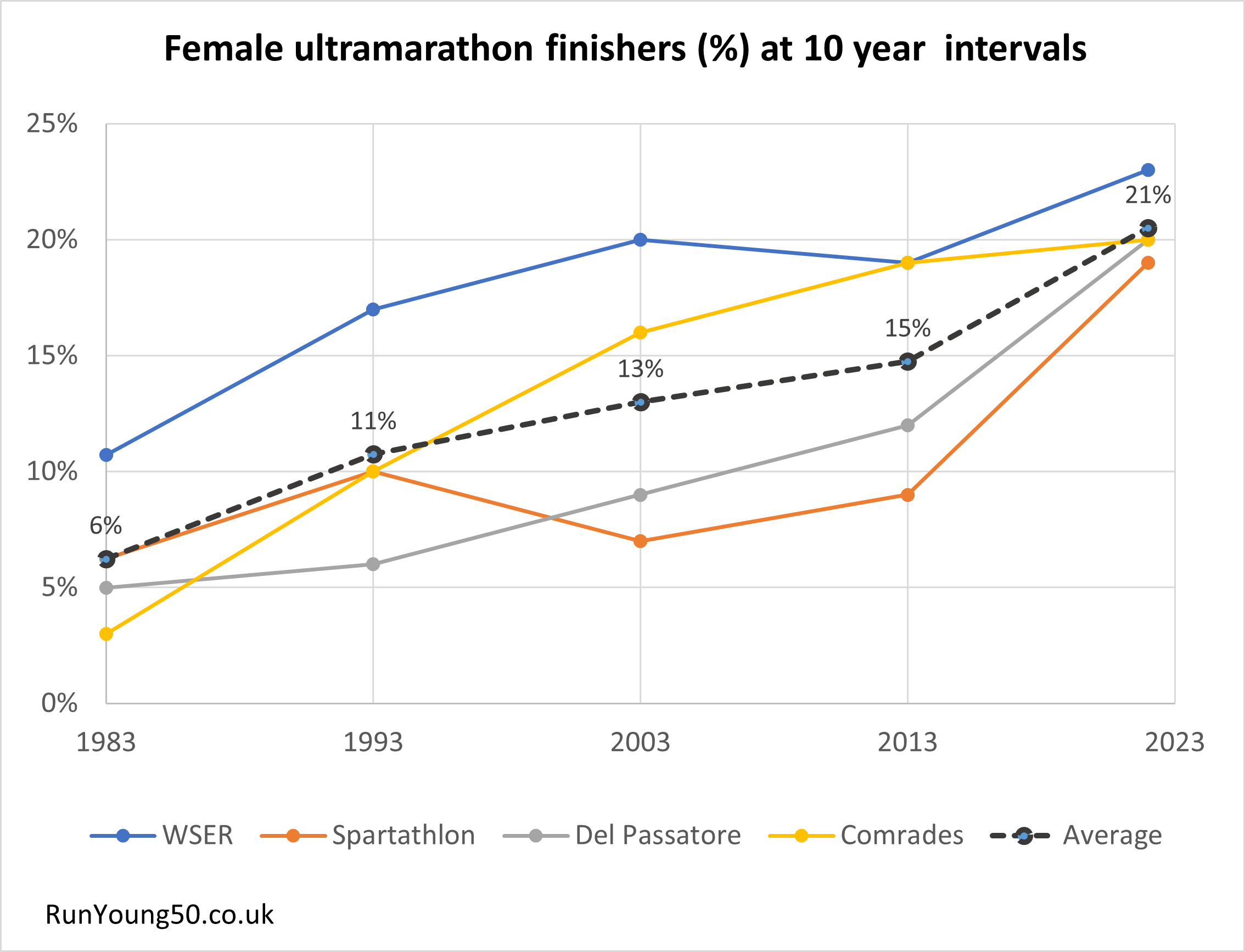

The graph above shows the percentage of female participants in the four of the ultramarathons that were held between 1983 and 2022. Percentages are at ten-year intervals with the exception of the last one as the results for 2023 are not yet available. I have omitted London to Brighton as it finished in 2005. Additionally, there is a line showing the average percentages across all four races.

This is a snapshot of the races at ten-year intervals rather than a full picture of participation over time. The average shows as three-and-a-half fold increase from 6% in 1983 to 21% female participation in 2022.

Did women’s participation increase steadily from a very low base in 1973? In the four races included in the graph, participation increased significantly from 1973, when it was less than 1%, to 1983 – 6%. The next decade also saw signficant growth with participation almost doubling at 11%. Two decades of slower growth followed, before a further significant rise in the past nine years, 2013-2022. London to Brighton had a different trajectory. Female participation remained very low, 5% in 1993, and then increased almost three-fold in the following decade.

Western States Endurance Run is the only race that had female participation of 10%+ in 1983 (11%). It has doubled its participation rate over 40 years.

Spartathlon and 100km Del Passatore both show a significant increase in the past nine years with Spartathlon doubling its female participation from 9% to 19% and Del Passatore increasing from 12% to 20%. Will these trends be maintained? Have the organisers of these races taken specific steps to encourage more women to participate?

The RunRepeat female participation figures for 2003 and 2013 were 17% and 19% respectively. These are higher than the average figures for these four races, 13% in 2003 and 15% in 2013. We might conclude that these races are lagging behind the international average. Western States is the only race to have achieved (in 2022) the 23% figure which RunRepeat found for 2018.

If the growth in female participation were continuing, we might expect that the 2022 figures for our races would be higher than RunRepeat’s 23% figure in 2018. However, it is 2% lower. It is possible that, due to gender inequalities, the Covid-19 pandemic may have affected women runners more than men, leading to a slowing in the growth of women’s participation3.

Gender inequalities

In an article for Outside Online in 2018, We Need to Fix Ultrarunning’s Gender Problem, ultrarunner Stephanie Case4 makes the case that “If we truly want more women in this sport, it’s time to change the system for entering races.” She points out that in ultramarathons with strict qualification requirements female runners rarely exceed 15% of the field. She identifies several reasons for the gender imbalance in ultrarunning. Girls are more likely to drop out of sport in their teenage years than boys. Some sports are perceived as inherently masculine, particularly those that involve extreme endurance. In ultrarunning, this may apply to longer distance events. For example, fewer women enter races over 100km. Women may have concerns for their safety. Societal norms around housework and childcare mean that women have less free time to train for races. Finally, women may be more self-selecting, they may be less likely than men to enter races for which they are not fully prepared. Case argues that one step race directors could take to redress the gender imbalance would be to give women a higher chance than men of getting places through lotteries.

Recent research study

A research study5 published in 2022 by academics from the University of the West of Scotland compared the experiences of male and female ultrarunners. Its findings were in line with some of the points Stephanie Case raised. The researchers looked at barriers to participation, as well as factors that enabled participation. The study included runners in the Scottish Jedburgh 3 Peaks ultra, a 38-mile race, and the Highland Fling, a 53-mile race which operates a ballot for entry. Women made up almost 50% of participants in the Jedburgh 3 Peaks ultra and around a third of participants in the Highland Fling. The study also analysed female participation rates in the 193 Scottish ultra-running events from 2010 to 2018. It found that “..although the proportion of female runners showed an increasing trend with time, female participation was generally lower in races of greater distances“. In all the races that were 50 miles or longer, female participation was below 30%. The race distance most likely to have female participation over 30% was under 40 miles. Finding time to train was the most common barrier to participation cited by both men and women. However, there were differences in men’s and women’s “negotiation efficacy” when it came to making time for training. Women with children were more likely to report prioritising the care needs of their children over their training, than men were. The authors suggest that despite a trend towards more equal parenting and sharing of domestic duties, women may still be affected by social expectations of mothers as the primary caregivers. Women may have a reduced sense of entitlement to leisure compared to men.

The She Races campaign – a woman’s place is on the start line

British ultrarunner Sophie Power took things several steps further than Stephanie Case’s proposal when she set up the She Races campaign in 2022. She Races aims to make racing more inclusive. The catalyst for the campaign was the refusal by the race organisers of the 2018 Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc to allow her a deferral three months after the birth of one of her children. The campaign is not limited to ultrarunning. It aims to make all types of races more inclusive by influencing organisers to bring about change. She Races has created a set of practical guidelines for race directors6. These are organised around three guiding principles:

- Level the start line – positive actions that can increase women’s participation, for example, using more inclusive imagery.

- Equal the experience – providing the facilities that women may need and creating a safe environment for women

- Respect our competition – giving equal recognition to the women’s race, for example, in media coverage

The campaign has already enjoyed success with major events changing their policies around pregnancy deferrals and providing facilities for breastfeeding mothers. Several companies have demonstrated their commitment to inclusion by signing up to the She Races event contract.

In conclusion

I am not sure that I will still be writing this blog in 2033, but it would be interesting to revisit the participation figures for these races in ten years’ time. It is a bit disappointing to find that none of these well-known ultramarathons is even near 30% participation. There could be several drivers for change. Firstly, as major races, such as UTMB, London Marathon and Ironman, change their policies to be more inclusive, this could have a trickledown effect on other events. It is harder to ignore the example set by a major event. Secondly, the grassroots, the smaller race organisers, may be quicker to recognise the benefits of being more inclusive. A number of smaller ultra events have signed up to the She Races event contract. They could drive change from the grassroots up. Thirdly, if the women who started running in their thirties, forties and fifties a decade ago, continue to run and move into ultrarunning, this could lead to more women taking part. When I started running in 2011, aged 47, it was to run five miles for charity. The idea that I would run an ultramarathon one day would never have entered my head. But training for and running the Crawley A.I.M Track 12 Hour Ultra in 2021 is one of my best running experiences to date.

Footnotes

- I do not know when Italian women were permitted to compete in long-distance races. On 31st December 1971, Paolo Pigni-Cacchi, who had set world records at 1500m, 5000m and 10000m, competed in the San Silvestro Marathon in Rome, finishing in 3:00:47.2 (see ARRS). This may have been an unofficial participation. Thank you to Monica Francioso Ideatrice of the Italian women’s ultrarunning website Donn&Ultra for telling me about this race.

- The Western States race website features history pages. The JFK 50 Mile is the USA’s oldest ultramarathon. It started as a closed club event in 1963. In 1968 Donna Aycoth was the first female finisher. The race started as a hike rather than a running event. Therefore, it presumably did not fall within the Amateur Athletic Union’s jurisdiction, meaning that women could participate. Aycoth ran the course. Read more on the Ultrarunning History website.

- For example, the UN report “COVID-19 Women, Girls and Sport: Build Back Better” (2020) noted: “The impacts of COVID-19 are already being felt harder by women and girls in many areas of life due to gender inequalities, and we see this mirrored in sport.“

- Stephanie Case is a Canadian human rights lawyer and ultra-trail runner. She founded the non-profit Free to Run which works with girls and young women in areas of conflict to develop female leaders through outdoor sport and adventure.

- S. Valentin, L. A. Pham & E. Macrae (2022) Enablers and barriers in ultra-running: a comparison of male and female ultra-runners, Sport in Society, 25:11, 2193-2212, DOI: 10.1080/17430437.2021.1898590

- The She Races guidelines are available here. In March 2023, Shane Ohly, Race Director for Ourea Events, the organisers of five multi-day UK trail ultras, wrote a thoughtful review comparing the She Races guidelines with the company’s policies and identifying where the company could improve its inclusiveness.

Links

Montane Winter Spine race website. In the shorter Spine Sprint and Spine Challenger North races 24% of the competitors were women.

My article on female ultrarunners over 50.

Comrades Marathon: the first series of Cherie Turner’s podcast, Women’s Running Stories, was dedicated to Comrades and includes an episode with Cheryl Winn who first ran the races in 1978 and won it in 1982. The story of Mavis Hutchinson is on the Ultrarunning History blog.

London to Brighton: Road Running in the UK in the 1950s and Leslie Watson’s story

100km Del Passatore: Eleanor Robinson’s 1991 win at the IAU 100km World Championship

Spartathlon: Eleanor Adams and the first Spartathlon

Western States Endurance Race: there’s a series of articles on the Ultrarunning History blog.

A look at marathons, motherhood and age – how elite runners are depicted in the media.

The She Races campaign.

Banner photo: a runner arrives at the finish line of the 100km Del Passatore in Faenza, 2018. Pmorelli1969, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments