The distance running history books

D’Amato isn’t the first mother to break the national record. For example, Sara Mae Berman (born 1936) was a mother of three in her early thirties when she set the record in 1969 and 1970.

Reading about D’Amato brought to mind another woman who broke a national marathon record at an age which was beyond the expected range for elite performance: British athlete Joyce Smith.

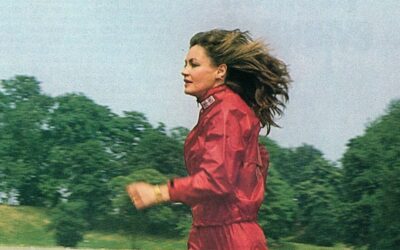

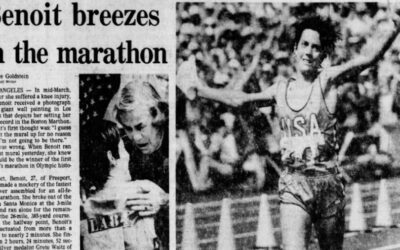

Smith (born 1937) was one of the world’s top marathoners in the early days of the women’s marathon. She retired from track in 1978, after a successful career which included the 3000m world best in 1971 and reaching the 1500m semi-finals at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games. Smith ran her first marathon in 1979, aged 41, winning it in a British record time. From then until 1982, she broke the national record five more times and became the first British woman to run under 2 hours 30 minutes when she won the inaugural London Marathon in 1981 in 2:29:57, the third fastest time ever run by a woman.

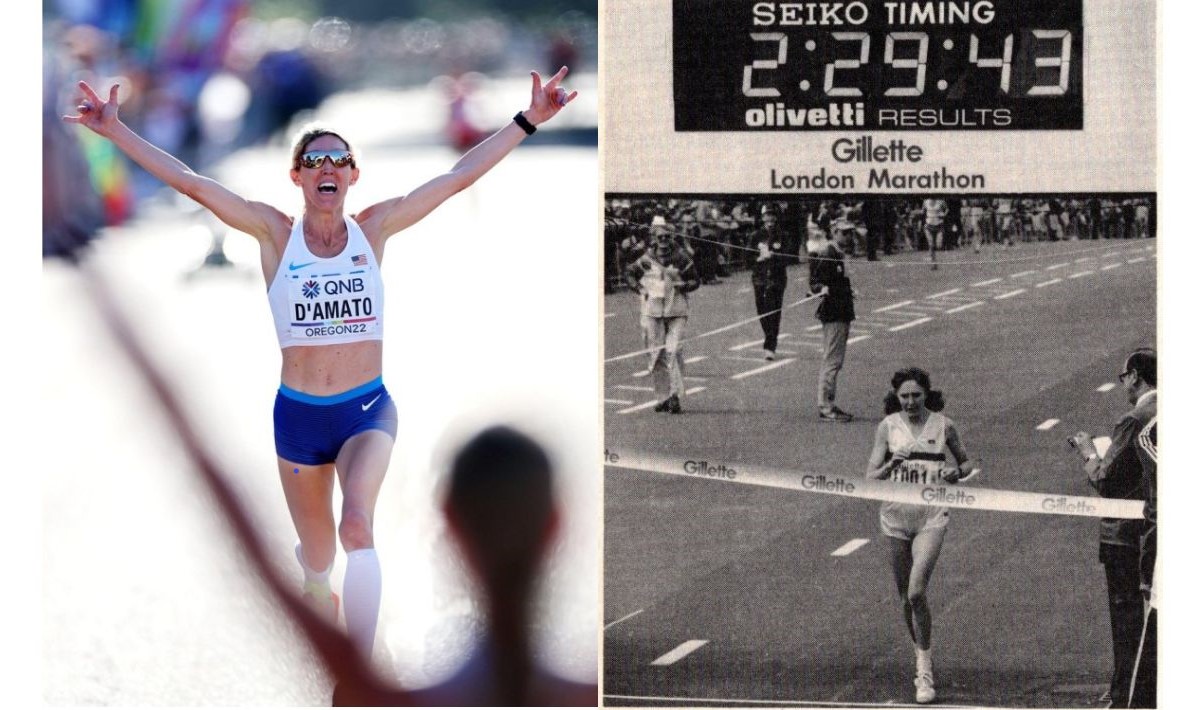

Keira D’Amato approaches the finish line of the Athletics World Championships Marathon, 18th July 2022. Aflo Co. Ltd. / Alamy Stock Photo

The significance of D’Amato’s record lies not in achieving something that has never been done before, but in pointing to how American distance running could change opening up new pathways and opportunities. Talya Minsberg’s vision is that this will be a future “in which runners are not expected to retire at 30, not disregarded upon starting a family, can control what success looks like and manage how they get there themselves.”

This article looks at how Joyce Smith and Keira D’Amato have been described by the media and compares this to coverage of male athletes.

Motherhood, running and gender norms

Running and elite performance are indicators of physical capital. Men and women acquire significant physical capital through reaching high levels of performance. For elite male athletes, this suffices to establish their status in the field of running. What else do we need to know about Eliud Kipchoge than his performances? An internet search returns phrases like “greatest male marathoner ever”, “marathon king”, “marathon legend”. I had to dig a bit to find out that he is married and has three children. His fatherhood is not even mentioned on his biography on the Abbott World Marathon Majors site.

Elite female athletes with children are more likely to be described as “moms” or “mothers” than purely in terms of their performance. For example, The Washington Post carried a long article about Keira D’Amato on 17th July 2022: “She’s 37. A mom of two. And America’s fastest female marathoner”.

Discrimination against pregnant athletes and new mothers

Professional American athletes who become pregnant have faced discrimination at the hands of sponsors who have cancelled or suspended their contracts. This was highlighted in 2019 by Alysia Montaño who has experienced discrimination both as a mother and as a black athlete. She spoke out about the way that her sponsors, Nike and Asics, failed to support pregnant athletes. In the UK, until this year, women with a Good For Age or Championship place had to take up their place in the London Marathon if they were 9 months postpartum. There was no option to defer. Following a campaign by athletes, the London Marathon has changed its rules so that all women who are pregnant or postpartum now have the opportunity to defer their place to a future London Marathon within a three-year window.

Marathon mums

In the past women athletes had little control over how they were described and categorised. Joyce Smith was routinely referred to as a mother in newspaper articles. Here are some examples from her peak performance years:

The Times habitually described her as Joyce Smith, (age), mother of two.

In January 1980, an article with the headline “Marathon mum gets the vote” in The Observer announced Smith as The Observer/Mumm Sports Personality of 1979. She was chosen over male athletes including Sebastian Coe. The award was made for “The almost unbelievable performance of this (now) 42-year-old marathon winning mother”. The article might have featured a photo of Smith competing in a race but instead it was accompanied by a photo of her with her two daughters Lisa and Lia.

On 17th November 1980, the Daily Mirror reported Joyce Smith’s win in the second Tokyo Women’s Marathon with the headline “It’s that mum again!”.

Sunday Mirror, 21st December1980, announcing her win in the 10-mile Hog’s Back road race: “Mother-of-two, Joyce Smith, Britain’s 43-year-old veteran women’s marathon record holder”

London Marathon winners, Athletics Weekly, 22nd May 1982

In contrast, Hugh Jones (born 1955), the men’s winner of the 1982 London Marathon is more often described by newspapers in terms of performance:

“Hugh Jones, the AAA marathon champion” The Observer 1982

“Hugh Jones, winner of the AAA Marathon, The Daily Telegraph 1982

“London marathon star” Daily Mirror 1982

Occasionally Jones is described as a Londoner and his age is given. It is hard to imagine any male athlete at that time being described as a father.

Reinforcing social gender norms

Constant references to motherhood reinforced social gender norms. Whereas for a man, “athlete” could be his core identity, for a woman it was her domestic role that defined her. No matter how good her performance it would always be viewed in relation to motherhood. When motherhood is foregrounded in this way, women’s social position is defined in relation to others. Women’s roles as mothers, wives/housewives and grandmothers define them and put them in their place in the social order.

Joyce Smith is still being described in this way. An article about her in The Telegraph on 25th April 2020 (the day before the 40th anniversary race would have been held) had the headline “Joyce Smith on winning first two London Marathons nearly 40 years ago as mother of two and running again in her 80s”.

Contrast that with the headline of an article about Eliud Kipchoge written by the same journalist, Ben Bloom, which appeared the day before in The Telegraph: “Eliud Kipchoge’s inside story: In camp with the greatest marathon runner”.

The Smith headline diminishes her achievements, whereas the Kipchoge headline reinforces his position at the apex of the marathon running pyramid, above all men and all women. Kipchoge could have been described as “the greatest male marathon runner” and Smith as “one of Britain’s greatest marathon runners”.

Motherhood and running – creating a new social capital?

Social media and personal websites may have given female athletes more control over their own narratives and how they want to be portrayed.

D’Amato uses her website to present her story and it features several medial articles about her success. Her Bio page features a family photograph. D’Amato’s Instagram account has over 53,000 followers providing her with a powerful tool to present herself.

When I used a search engine to look for media articles about D’Amato, I found fewer references motherhood than I had expected. It was a somewhat limited search, but it suggests that referencing motherhood is not the norm now in the way it was for Smith.

Women runners have used social media and websites to build online networks in line with their preoccupations and interests. Some of these have centred around motherhood. Two examples with large engagement are the USA-based Another Mother Runner and the UK-based Run Mummy Run. Both also have podcasts.

Some running bloggers include their role as mother or grandmother in the name of their blogs. The Feedspot list “Best Women’s Running Blogs and Websites” lists 98 websites. 8% have names relating to motherhood, such as “Half Crazy Mama” and “Mommy Runs It”.

This raises the question as to whether women are continuing to conform to expected social norms by identifying themselves as “mother runners” or whether they are creating social capital for themselves with a new social status. What is the impact of asserting this identity on women who have not joined the “motherhood club”?

Age and running

Joyce Smith’s career shows that elite marathon performance in a woman’s late thirties or forties is possible. She is not unique. Priscilla Welch (born 1944) was 42 when she set a British marathon record of 2:26:51 at the London Marathon in 1987, a time which still ranks seventh on the British all-time list. Australia’s Heather Turland (born 1960) was 38 when she won the 1998 Commonwealth Games Marathon in Kuala Lumpur. Mara Yamauchi was 35 when she ran 2:23:12 at the London Marathon in 2009, the third fastest time on the British all-time list.

It would be interesting to understand whether there is more focus in the media today on the age of female athletes than there is on men’s age. Is there a preconception that men can carry on competing at elite level for longer than women?

D’Amato’s age was one of the first things I knew about her. In contrast, Eliud Kipchoge’s age is rarely mentioned – he is 37. British marathon runner Chris Thompson was a surprise winner of the men’s British Marathon Trials in 2021 at the age of 39 and went on to compete at the Tokyo Olympics aged 40. This was remarked upon as a particular achievement because of both his age and his injury-disrupted running career.

D’Amato’s ambition of representing the USA in an international championship became a reality when she was offered a place on the World Championships team after Molly Seidel was forced to withdraw due to injury. She finished 8th in the Women’s Marathon in Oregon on 18th July 2022. According to The Washington Post article D’Amato is looking to qualify to compete in the Paris Olympic Games in 2024. She can take heart from Joyce Smith’s example: Smith competed in the inaugural women’s marathon at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, finishing 11th in 2:32:48 at the age of 46.

Non-traditional running careers

Keira D’Amato was a successful track runner who was recognised as an outstanding athlete at university (and was bestowed with the honorific title “All-American” four times). After graduating, she joined a professional running team. D’Amato was forced to retire from competitive running after a bone deformity in her foot ended her track career. During this extended break she had her two children and developed a career in real estate. Unlike many other athletes, she was not dependent on sponsorship and, when she took up marathon running, she was able to support herself financially. This placed her in a strong bargaining position when she was approached by potential sponsors following her rapid improvement at the marathon distance. D’Amato was able to negotiate a contract with Nike which suited her and did not require her to move or to take a different coach.

Joyce Smith’s route into long-distance running was unconventional because she had no opportunity to run marathons in her thirties. In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common for female track athletes to retire in their twenties, often on getting married or starting a family. This was no doubt partly driven by social expectations but also reflected the fact that there was no option to move on to long-distance running, an option that was available to men. Smith had continued her elite track career into her thirties. She made the most of the opportunities that became available to her as women’s distance running developed following the lifting of the ban on women’s distance running in the UK in late 1975. These new opportunities motivated her to keep competing and extended her career as an elite athlete.

“Because the events slowly came in, I just moved up a step each time and it was a new event, a new achievement. There was always something new to do….New horizons kept opening up.”

Smith had limited opportunities for sponsorship and prize money as athletics was still amateur, although rapidly moving towards professionalism. In 1982/83 she was a member of the Evian Marathon Squad, established by the British Amateur Athletic Board and the Women’s Amateur Athletic Association. Athletes chosen for the squad had access to free running gear, training camps and coaching, along with a generous supply of Evian mineral water.

Looking forward

In a blog post on the Citius Mag website, David Melly points out that Keira D’Amato’s story challenges American sponsors, team selectors and the public to re-think their preconceptions about what makes an elite marathon runner.

The problem is that we’ve focused our norms too narrowly…We need to make space in the sport for more unconventional runners to thrive…We need to normalize taking breaks…

Keira D’Amato’s story and accomplishments are remarkable, but runners like her don’t have to be as rare as they are currently. Rather than seeing the working-mom elite runners of the world as unicorns to be placed on a pedestal and marveled at, let’s create a system that makes them commonplace.

The analysis of the way Keira D’Amato and Joyce Smith have been described in the media shows that much has changed, but also suggests that gender norms around motherhood and age still limit public perception of elite female athetes’ potential.

Notes and References

More posts on the history of the women’s marathon

“Milestones in Women’s Marathon History – Permission for Women to run the Marathon in the UK” by Katie Holmes, Playing Pasts website, 25th July 2022

“Keira D’Amato and Sara Hall Rewrite the Distance Running History Books” by Talya Minsberg, New York Times, 19th January 2022

Keira D’Amato’s website

Keira D’Amato’s World Athletics profile

Pioneering marathon runner Joyce Smith – “I was a little bit before my time”

Joyce Smith’s World Athletics profile

Eliud Kipchoge’s profile on Abbott World Marathon Majors website and Wikipedia profile.

“Alysia Montaño is the Hero of this Story” by Nicole Blades, Runner’s World magazine (US), 26th August 2020

“London Marathon changes policy for pregnant and postpartum participants” by Jenny Bozon, Runner’s World magazine (UK), 21st July 2022

“What Keira D’Amato’s Story Tells Us About Elite Running” by David Melly, Citius Mag website, 17th January 2022

“First Ladies of Running” by Amby Burfoot, Rodale, 2016

“Running, Identity and Meaning – the Pursuit of Distinction Through Sport” by Neil Baxter, Emerald Studies in Sport and Gender, 2021 (includes a discussion of cultural capital and the field of running)

“Sporting females – critical issues in the history and sociology of women’s sports” by Jennifer Hargreaves, Routledge, 1994.

0 Comments