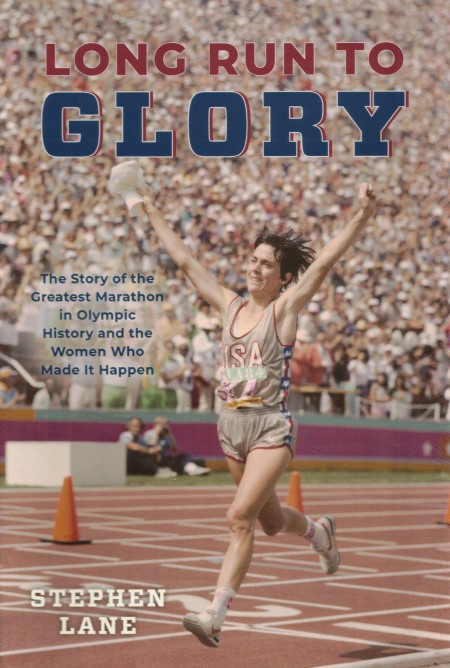

Stephen Lane’s book “Long Run to Glory” is timely. The Paris 2024 Olympic Games will mark the fortieth anniversary of the first women’s marathon at the Olympics. The race was held at the Los Angeles games on 5th August 1984, 88 years after the first men’s Olympic marathon. Long Run to Glory gives us an extended narrative of the events that led to the first Olympic Marathon and a detailed account of the race.

Several books have covered parts of the story. For example, Kathrine Switzer’s memoir “Marathon Woman – running the race to revolutionise women’s sports” and Jacqueline Hansen’s “A Long Time Coming – Running through the women’s marathon revolution”. Both women were early marathon runners with Hansen twice setting the world record. But it is their contribution as campaign leaders that is foregrounded in Long Run to Glory. Additionally, many of the key players in Lane’s book have been interviewed and profiled many times. For example, in Amby Burfoot’s “First Ladies of Running”.

So, the story has been told before in parts but it has not been the subject of a book. Long Run to Glory brings together the different elements into a cohesive account of the path to the first women’s marathon at the Olympics.

Long Run to Glory – Parts I & II

Following a short introduction, a prelude gives an overview of the inclusion of women’s athletics events in the Olympic Games for the first time at the 1928 Amsterdam Games. An account of the 800m race provides context for the limitations placed on women’s running. The reporting of the race was used to justify the removal of the 800m from the women’s programme until 1960.

Long Run to Glory is divided into four parts.

Part I covers the period from 1966, when Bobbi Gibb raced unofficially in the Boston Marathon, to 1981, when the IOC finally agreed to add the women’s marathon to the Olympic programme. The development of women’s distance running in the USA coincided with the growth in the popularity of jogging and the first years of the New York Marathon. Part I also covers the roles that Nina Kuscsik, Switzer and Hansen played in getting the women’s marathon accepted onto the Olympic programme. The impact of the Avon International Running Circuit, established by Switzer, and the International Runners Committee, led by Hansen, are explained. In the final chapter, “Victory”, Lane does a good job of documenting the tortuous negotiations required to get the change approved.

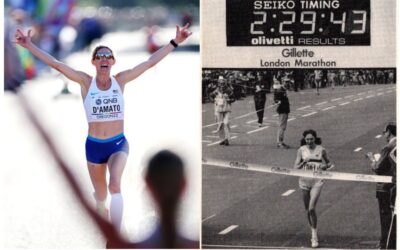

Part II is primarily focused on the development of Grete Waitz’s and Joan Benoit’s marathon running from 1981 to 1983. They are set up as the main characters of the remaining narrative. Part II also touches on Patti Catalano, the first American woman to run under 2 hours 30 in the marathon, and New Zealander Allison Roe. After Roe won the Boston Marathon in 1981, Fred Lebow, director of the New York Marathon saw her as a natural rival to Waitz. Lane includes an account of the 1982 European Athletics Championships marathon which was seen by some as a test event prior to the Los Angeles Olympiade. Rosa Mota of Portugal won the race and Ingrid Kristiansen of Norway finished third. They are positioned as serious contenders for the 1984 race.

Long Run to Glory – Parts III & IV

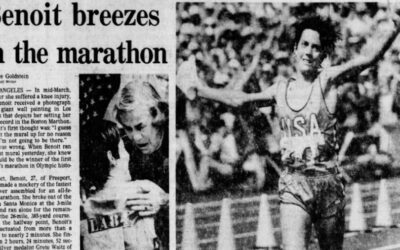

The first three chapters of Part III focus on the U.S. Olympic Trials held on 12th May 1984, and the setbacks which Benoit experienced which jeopardised her participation. It also describes the performances in key races of the other three main contenders for the Olympic race, Waitz, Mota and Kristiansen. The final two chapters cover the Los Angeles Olympic Games and an account of the women’s marathon race. A final interlude at the end of Part III narrates the dramatic finish of the Swiss athlete Gaby Andersen-Schiess who was severely dehydrated.

Part IV consists of three chapters covering key dates in the careers of the four top finishers after Los Angeles until the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, and their later lives. A postlude describes the bond that persists amongst the American “pioneer generation” of women, the runners who came before Benoit and Waitz.

Vivid descriptions

Long Run to Glory is engaging and well-written. Many of the descriptive passages are vividly written with a lot of detail, giving the reader a sense of the experience of “being there”. An example is the final chapter of Part III, entitled “The Race”, which picks up the account of the Olympic marathon from the two-mile point. The detailed account of the progress of the race is enlivened by descriptions of some of the sights and sounds along the course. Lane describes the street scene at the 5k-to-go point:

The noise is loudest since the start. …people spill off sidewalks, waving flags, or towels if the don’t have flags. …Dads hold up babies. People are dancing.

The account is interspersed with descriptions of the runners’ emotions and sometimes their thoughts. For example, Benoit in the lead at the 5k point:

For a moment, Benoit worries she’s making a major blunder: you’re going to look real stupid, she says to herself, if you take the lead now, then die and get passed later on.

We all know the outcome of the race, much has been written about it, and the whole book has been building up to it. Despite this, Lane manages to make this chapter a pacy and exciting read. Having profiled the race leaders in the earlier chapters, he focuses on how each of those runners performs and feels during the race. It made me want to watch the TV coverage as I now have a commentary which puts the race in its historical perspective.

Well-researched

Long Run to Glory appears to be well-researched. In the Acknowledgements, Lane mentions many sources of information, including archives, and people he interviewed for the book. The book has an index and endnotes. Sports historians may be frustrated by the omission of a bibliography. The endnotes provide some sources.

Although, as noted above, the key elements of the story have been written about before, most readers will still find much information they were not aware of. I was interested to learn that top female marathoners of the 1980s sometimes attracted higher appearance fees than men at American marathons. Lane writes of Benoit, Waitz, Mota and Kristiansen, “…they received top billing at major races, pushed the men out of the headlines, and commanded greater prize money”. He gives the example of Grete Waitz receiving the highest appearance fee for the New York Marathon in 1985. And a sponsor of the Chicago Marathon that year offered Benoit $150,000 on top of the race organiser’s appearance fee.

I particularly enjoyed the account of how the small town of Olympia in Washington was chosen as the host of the first-ever American Olympic Women’s Marathon Trials. This was mainly thanks to the effort of entrepreneur Laurel James, who had set up a successful running store in the late 1970s. The citizens of Olympia became enthusiastically engaged in the preparation and delivery of the event which became a celebration of women’s running.

USA-focused

This book is focused on the USA, with the Boston Marathon and New York Marathon as the main events in the lead up to the Olympic marathon. There are some exceptions. For example, Dr. Ernst van Aaaken’s Interational Women’s Marathon in Waldniel, West Germany in 1974, and the Tokyo International Women’s Marathon in 1979. Although three of the four main protagonists are not American, much of the focus is on their participation in American marathons. As the USA was in the forefront of the development of the women’s marathon in the 1970s, this focus is not unjustified, but it would be interesting to know more about the international picture.

A feminist perspective

Lane highlights the importance of running as a form of liberation for women. He describes it as “a sisterhood, a movement and part of an athletic awakening across all women’s sports”.

There were a couple of passages in the book that jarred with me, where Lane appeared to accept, rather than challenge, contemporary narratives. The first is the story of Switzer and Jock Semple, codirector of the Boston Marathon who Lane describes as “famously foul-tempered”. Semple assaulted Switzer when she ran in the 1967 Boston Marathon. Switzer had broken the rules by acquiring a race number and Semple attempted to remove her numbers by force whilst shouting angry abuse. Lane notes that this behaviour would be unacceptable today. Yet, he sentimentalises Semple. Six years later, Semple approached Switzer on the start line of the 1973 Boston Marathon. It was the second year that women had been officially permitted to race. Semple decided to create a photo opportunity for the press, and without asking her permission, put his arm around Switzer and kissed her on the cheek. Lane concludes, “Their world had changed; his bit o’notoriety was a stubborn man’s way of admitting that he had been wrong, of asking forgiveness…“. Describing Semple as “a stubborn man…asking forgiveness” downplays the violent nature of Semple’s assault on Switzer. And whilst Lane sees the 1973 episode as a cosy moment, it also reflects a power dynamic where Semple knew he could embrace Switzer in front of the press with little risk of being rebuffed by her or criticised by others.

The second passage is the description of Allison Roe which repeats several contemporary statements by men about her looks. Lane comments, “Even years later, she seemed fixed in longing male memories.” This passage validates the sexual objectification of Roe. Rather than confronting this, Lane says, “So much attention on her appearance embarrassed her, but she rolled with it, even though those who focused on her looks missed so much.” Roe probably had no choice but to “roll with it”.

Sexual assault and objectification are still issues for many sportswomen today.

Conclusion

Long Run to Glory tells an important story in an engaging way with well-researched detail. It will resonate with the audience for the 2024 Paris Olympics Games and in 2028 when the Games return to Los Angeles.

Thank you to Stephen Lane and his publisher, Lyons Press, for sending me a review copy of the book.

Notes

Long Run to Glory – The Story of the Greatest Marathon in Olympic History and the Women Who Made It Happen, Stephen Lane, Lyons Press, 2023 – 274 pages with 8 pages of black and white photographic images

Marathon Woman, Kathrine Switzer, Da Capo Press, 2007

A Long Time Coming, Jacqueline Hansen, self-published

First Ladies of Running, Amby Burfoot, Rodale, 2016

Read more on the blog about:

The women’s marathon in the 1960s

Kathrine Switzer

Jacqueline Hansen

The introduction of women’s running events in the Olympic Games

Women’s marathon history

0 Comments