Fifty years ago there was virtually no opportunity for women to take part in endurance running, let alone run a marathon. Women were prohibited from running further than 200 metres at the Olympics from 1928 until 1960 when the 800 metres was added. It took another 12 years before the 1500 metres featured in the programme and the women’s marathon was not added until 1984, 88 years after the first men’s Olympic marathon.

How have we gone from no women marathon runners fifty years ago to more than 40% of finishers in the USA today?

There is no doubt that this huge uptake in women running would never have occurred without the pioneering women distance runners who broke the mould in the 1960s and 1970s. Sometimes these women “gatecrashed” men-only races, sometimes they were one a handful of women in a field of more than a thousand men, sometimes they weren’t allowed to race. Many of them did not get the opportunities to compete that they deserved, but they became the activists who changed the rules, who battled with the athletics governing bodies, who brought the lawsuits and paved the way for all the women runners at half marathons and marathons today.

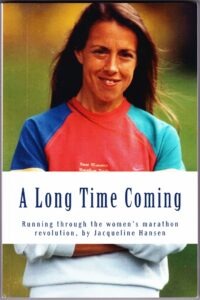

Jacqueline Hansen was one of these marathon pioneers. She was at the heart of this struggle for change for two decades both as an elite athlete and an activist. Her book “A Long Time Coming – Running through the Women’s Marathon Revolution” chronicles both of these trajectories. Hansen’s importance as a pioneer is highlighted by Joan Benoit Samuelson, winner of the first women’s Olympic marathon in 1984, in her foreword to “A Long Time Coming”.

Jacqueline Hansen was one of these marathon pioneers. She was at the heart of this struggle for change for two decades both as an elite athlete and an activist. Her book “A Long Time Coming – Running through the Women’s Marathon Revolution” chronicles both of these trajectories. Hansen’s importance as a pioneer is highlighted by Joan Benoit Samuelson, winner of the first women’s Olympic marathon in 1984, in her foreword to “A Long Time Coming”.

“I am sometimes referred to a ‘pioneer’ for having won that gold medal. I appreciate the thought, but gently point out that I was not one of the pioneers. Instead, our inaugural race in Los Angeles was made possible by the efforts, both physical and political, of earlier women marathoners. They broke down the barriers of intolerance and indifference, starting long before 1984.”

Elite athlete

Jacqueline Hansen set the world marathon record twice, first in 1974 when she became the first woman to run under 2 hours 45 minutes and then again in 1975 when she broke 2 hours 40 minutes. In October that year she ran 2:38:19 at the Nike Oregon Track Club Marathon in Eugene, Oregon.

Born in 1948, her athletic career started with track running in high school at a time when the longest distance girls could compete at was 440 yards. She trained and competed with track clubs but was always drawn to longer distances. In 1971 after seeing her teammate Cheryl Bridges compete in the Western Hemisphere Marathon in Culver City, setting a new world record time, Hansen vowed to run it herself. “I could not help but think that I could do what she did.” True to her word Hansen ran the race the next year, winning it in a time of 3 hours 15 minutes. Her longest run in preparation for the race had been 14 miles and on the day she hadn’t even told her family that she had entered.

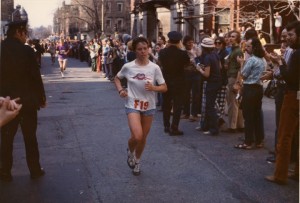

The turning point in her career came when she won the Boston Marathon in 1973.

“My running career took a new turn and forever changed my life. I had found my event (and would go on to win 12 of my first 15 marathons).”

Winning Boston in 1973

Her win attracted considerable media attention and launched her career as an elite athlete. Shortly afterwards she received her first invitation to compete in a major road race, and many more invitations followed. In 1974 Hansen competed abroad for the first time, in the first International Women’s Marathon in Waldniel, West Germany, organised by Dr Ernst Van Aaken, an early proponent of endurance running for women.

Hansen’s peak years were from 1973 to 1975, culminating in her second world record marathon time in October 1975 in a race she experienced as “effortless and euphoric”. After 1975 although she continued to compete at a high level and win races she never regained this peak performance. Hansen reflects that those three years had a hectic schedule of races and that this certainly contributed to the health problems and injuries which hampered her running in subsequent years.

“In retrospect I realize I must have been accepting too many invitations and running races too close together, with too much traveling. Perhaps being the world record-holder led me to believe I was Wonder Woman. I found out the hard way that when you are at the top of your game, it’s a fine line you are straddling as you’re vulnerable to falling over the edge.”

Activist

Jacqueline Hansen was moved to act by her own personal experience which made the overwhelming injustice so real and so concrete. She writes that in 1974:

“I was keenly aware by now that my new distance events did not afford me the opportunity to try out for the Olympic team…I came to realize the injustice of having no place to advance to the highest level of the sport. Naively I imagined that a few letter-writing campaigns, circulating petitions and speaking out in the media would ‘get the job done’. Little did I know that it would be a 10-year ordeal before seeing the marathon in the Olympics.”

I suspect that part of Jacqueline Hansen’s motivation to write her book came from a desire to honour the many other women who played a role in changing athletics. The feminist movement of the 1970s was a major impetus and source of support for the campaign that Hansen and many others engaged in. As the decade progressed there were increasing opportunities for women distance runners, including a growing number of women-only races in the USA, but the international athletics governing bodies were slow to change. Hansen’s husband, Tom Sturak, a Nike employee, was instrumental in persuading the company to promote the cause of women’s distance running. This led to Nike forming the International Runners Committee in 1979. The Committee’s role was to lobby international governing bodies to include women’s distance events in the Olympics and new World Championships which were due to begin in 1983. Their campaign was not just about the marathon but also the 3,000 metres, 5,000 metres and 10,000 metres events.

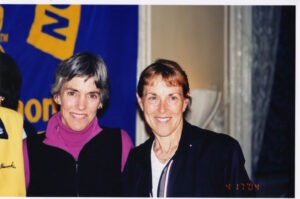

Jacqueline Hansen was the President of the International Runners Committee and there were representatives from the USA and Brazil, West Germany, Hungary, New Zealand, Japan and Great Britain. The British representative was Lyn Billington.

In 1980 the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) recognised the 5,000 metres and 10,000 metres as distances for women; this meant that women’s world records at these distances would be officially recognised and recorded for the first time. The IAAF also decided that the women’s marathon would be included in the inaugural IAAF World Championships in Helsinki in 1983.

It took several more months of lobbying and wrangling before the International Olympic Committee finally agreed in 1981 to add the women’s marathon to the 1984 Olympics programme. The 3,000 metre race was added at the same time (men ran the 5,000 metres).

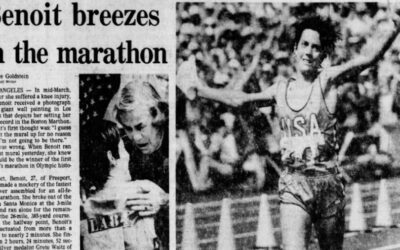

Hansen describes her experience of supporting Joan Benoit on the momentous day of the first Olympics women’s marathon in Los Angeles in a chapter entitled “Golden Day in L.A.”. This was a significant day not only for the athletes but for what it represented for all women.

“As I watched this dream unfold that day, it occurred to me that young girls all over the world were watching Joan Benoit on television, winning the Olympic Marathon, knowing they too could grow up to be Olympic champions if they wanted. They could dream of being presidential candidates and astronauts, too. It was an exciting time to be a woman.”

Joyce Smith ran for Great Britain in this race aged 46, finishing 11th, just under 8 minutes behind Benoit.

Whilst the decision to include the women’s marathon was a huge victory the battle for equality was not over, as the 5,000 and 10,000 metre distances were still left out. Despite having recognised these distances the IAAF was not willing to make the case to the International Olympic Committee for their inclusion. Hansen relates how two top IAAF officials told her at the time that these women’s races would be boring events that wouldn’t sell tickets. (How wrong they were!)

The campaign continued and in 1983, as a last resort, Jacqueline Hansen worked with the American Civil Liberties Union and the International Runners Committee to bring an international discrimination case on the grounds that women had access to only a third the numbers of events at the Olympics that were available to men. The aim was to force the IOC to include the races in the 1984 Olympics. The lawsuit was rejected in April 1984 and a subsequent appeal was turned down, but the campaign had now gained such publicity that the IOC had to give way. It was too late for the Los Angeles games but the first women’s 10,000 metres was run at the Seoul Olympics in 1988 and in 1996 the women’s 5,000 metres replaced the 3,000 metres at the Atlanta Olympics.

Educator and coach

Jacqueline Hansen starting the elite women’s race at the 2013 Boston Marathon on the 40th anniversary of her win

Jacqueline Hansen began coaching in 1987, working as US women’s head coach on several trips abroad and also coaching children at her son’s elementary school. She retired from running in 1992 and later gained a Masters degree in Education and went on to teach health education. Athletics has continued to be at the heart of her life. I am struck by her dedication and devotion to giving others the opportunity to achieve their potential, particularly young people and not just the highly-talented ones. This is exemplified by her recent participation in the Special Olympics in 2015 which she describes in her blog as “an inspirational and fulfilling experience”.

Final thoughts

I found out about “A Long Time Coming” when I found an article on Jacqueline Hansen’s website about the history of women’s marathon running. I was keen to read her book to find out more about how the battle had been fought to get the women’s marathon included in the Olympics. I also wanted to understand what it was like to compete in endurance races in the 1970s and 80s. How many women were running in those races and who were they? Reading Hansen’s book and writing this article have both added to the picture and raised more questions. I want to find out more about women’s experiences and more about the development of women’s distance running in the UK. It has reminded me of my original intention when I set up this blog: to interview older women runners about their experiences. I hope to find women who ran in the 1970s in the UK and learn more about what it was like for them. If you are one of these women please do get in touch.

I may never run a marathon and I will certainly never win a race but I hope that I share some of Jacqueline Hansen’s determination.

With kind thanks to Jacqueline Hansen for permission to use photographs from her website www.jacquelinehansen.com

Race gatecrashers included: Bobbi Gibb, in 1966, was the first woman to finish the Boston Marathon. She stood at the side and joined the race just after the starting gun was fired.

Runners who were part of a handful of women competitors: in 1972 the Boston Marathon officially admitted women for the first time. Nine women and 1,200 men entered the race. By the end of 70s the percentage of women entrants had risen from less than 1% to nearly 7%.

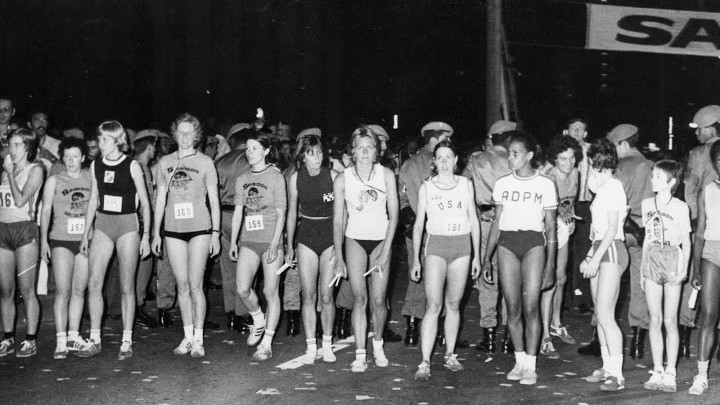

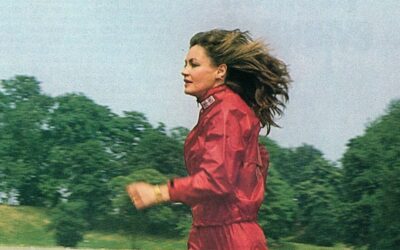

Women excluded from races: the banner photo is of the long-established Sao Silvestre midnight New Year’s Eve run in Sao Paolo, Brazil. Jacqueline Hansen was instrumental in getting women runners included in the field and persuaded some of the best female runners in the world to take part. She is pictured here on the start line (wearing USA vest) in the inaugural women’s race in 1975.

US participation data from Running USA website and international marathon data from RunRepeat.

Facts about Boston Marathon history from Boston Athletic Association website.

Other posts about the history of women’s endurance running:

Joyce Smith – winner of London Marathon & Tokyo Marathon

Kathrine Switzer – first woman to run with numbers at Boston Marathon (1967)

“Nike is a Goddess” – a history of women’s involvement in sports from 1880s to 1990s

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks