On a sunny day in August 1980, 200 women from 27 countries lined up in Battersea Park in London to run a marathon. It was the first time the city’s streets had ever been closed for a race.

It was the 3rd August. Two days before, the men’s marathon had taken place at the Moscow Olympics. But there was no women’s marathon in the Olympic programme. Women’s distance running was not recognised by the world’s greatest sporting event. The furthest distance women could compete at in the Olympics was 1500m. This distance had been included for the first time for women eight years before at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

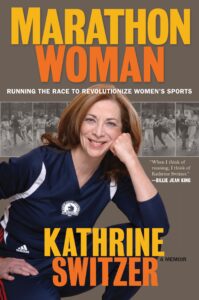

The London women’s marathon was the third in a series of marathons sponsored by the Avon cosmetics company. The Avon International Running Circuit was the brainchild of Kathrine Switzer. Avon took her on in 1977 to manage their rising stars women’s tennis circuit, and she successfully made the case for the company to sponsor a marathon race for women. The first Avon International Marathon took place in Atlanta, Georgia, in March 1978. It was the starting point for the development of the Avon International Running Circuit. Over its eight years of existence it gave over a million women the chance to run a range of distances. Many of the women were competing for the first time. Twenty-seven countries hosted over 200 events.

The London International Women’s Marathon

Switzer enlisted the help of local running clubs to plan the route and organise the race. She had plenty of experience of working with running clubs and race organisers in the United States and their participation was undoubtedly critical to the success of the race. In her book she mentions Bryan Smith (Barnet & District AC), who was Race Director, Paul Lovell (Highgate Harriers), Dave Billington and Vera Duerdin. Sir Horace Cutler, Leader of the Greater London Council (GLC), gave his permission and his active backing to ensure that the race could happen.

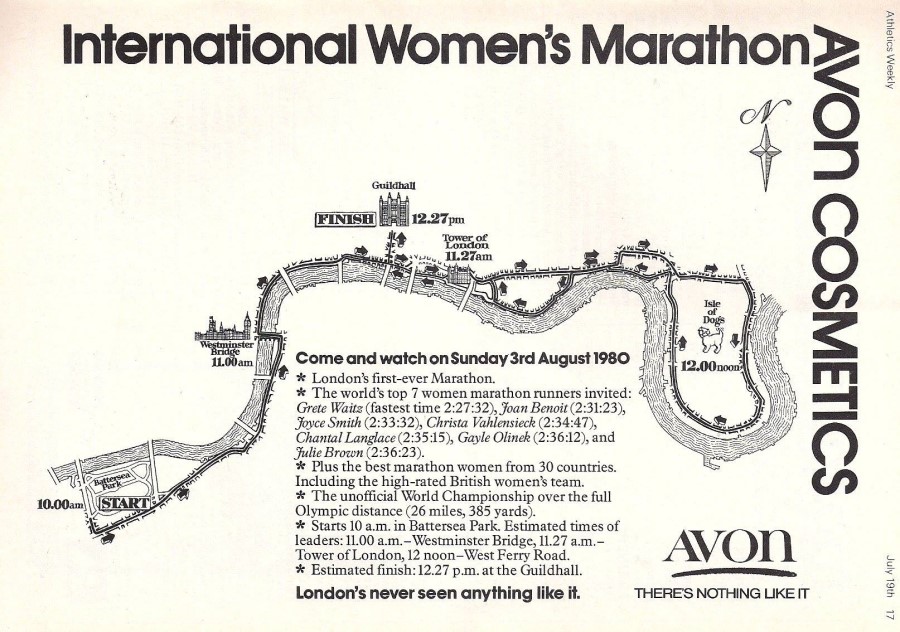

The route started at Battersea Park, south of the River Thames, and finished at Guildhall in the City of London financial district. After running three laps of Battersea Park (about 14km), the runners skirted the south bank of the Thames before crossing Westminster Bridge. The rest of the course was on the north bank of the river, passing the Tower of London, going out to, and round, the Isle of Dogs, before running back west along the river to the Tower of London and turning north into the City to finish at Guildhall.

Advertisement for the London Avon International Women’s Marathon with a list of names of runners who’d been invited and a map of the course, Athletics Weekly 19th July 1980

Who ran in the London Avon International Women’s Marathon?

Promotional photograph of some of the runners on Westminster Bridge (Arthur Klonsky)

Some of the 200 competitors had won their places through accumulating enough points in shorter races in the Avon Running Circuit series, or as prizes in other races. Others were elite athletes who were invited to run. These included Joan Benoit and Gail Volk from the US, and Lorraine Moller from New Zealand.

An Avon representative was selected to run, Jean Britton from Essex. In an article from The Guardian’s Women’s Page published the day before the race, Britton says that she had only started training two months before when she had heard about the race. Her ambition was to run at least 13 miles.

The partial results list on the Association of Road Racing Statisticians website states that 155 runners completed the marathon. In addition to the US, UK and New Zealand, it lists competitors from 12 countries: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

There was extensive coverage of the race in Athletics Weekly in the 16th and 23rd August issues. Athletics Weekly stated that 145 women completed the course within 4 hours. In the results (which cover the first 104 finishers), the Netherlands, Norway and the Republic of Ireland also feature.

Race favourite Joyce Smith

Joyce Smith winning the second Tokyo International Women’s Marathon in November 1980

One of the favourites on the day was Joyce Smith, the British record-holder. Smith was coached by her husband Bryan, the Race Director. She had won the second Avon International Women’s Marathon in Waldniel, Germany, the previous year. However, Kathrine Switzer notes in her book, “Marathon Woman”, that Smith had only just recovered from catching chicken pox from her daughter and was probably not on her best form that day.

The New Zealander Lorraine Moller won the race in 2:35:11, having passed the race leader, American Nancy Conz, at 21 miles in the Isle of Dogs.

It was a New Zealand national record and the seventh-fastest time run by a woman. Moller was a track athlete who had started distance running after moving to the United States in 1978. Nancy Conz finished second and Canadian Linda Staudt took third place, having overtaken Joan Benoit close to the end of the race. Joyce Smith was the first British finisher in seventh place.

I’ve not been able to find out whether Jean Britton made it to the end of the race.

Top ten finishers

This list comes from Athletics Weekly, 16th August 1980.

Spectators’ accounts

William Scott, a member of my running club, was a spectator on the day. William started running around this time, and thinks he may have read about the race in an athletics magazine or in the press. He cycled with his neighbour from his home in Highbury to Guildhall to watch the finish. They saw a lot of the finishers, including the winners. William told me it wasn’t at all busy at the finish. There were only about 40 people there, and he thought most of them were the organisers. William and his neighbour were able to stand next to the course with their bikes to see the runners come past. He told me that his impression at the time was that these were all top class competitors, “the idea of ordinary people running marathons didn’t exist back then”. William went on to run many marathons himself, with his first one being in June 1981.

If they could do it, so could I!

Catherine lived near Battersea Park and saw the race start being erected. She had heard about the marathon in Jogging magazine and she was interested in the idea of running a marathon herself, even though not many people ran marathons at the time. Catherine was at the start and then cycled into the City to watch the finish. She remembers being able to stand near the front at the start and she recognised Joyce Smith. There weren’t many people there but there were lots of Avon staff in their red T-shirts. Some of them started off in the race but Catherine thought they didn’t look as if they’d done much training. At Guildhall, Catherine was impressed by how well the leaders looked as they approached the finish line. Catherine said,

“It was this event that got me interested in running marathons. It was the less fit women in the Avon race who inspired me. If they could do it, so could I!”

Catherine tried to get a place in the 1981 London Marathon but wasn’t quick enough getting her entry in. Her first marathon was the 1981 Cornwall Marathon (Lands End to Redruth) which took place on the same day as the London Marathon. She went on to run seven more marathons, including London. Catherine inspired her husband to take up distance running and both her sons are runners. She said, “That Avon London Marathon had a lasting influence.”

British competitors

The Guardian article notes that “less than half the 200 competitors are British”. This suggests there was quite a depth in the British women’s marathon field. The Women’s Amateur Athletic Association (WAAA) had introduced a Women’s Marathon Championship in 1978 and nominated the Avon marathon as the 1980 championship event. The top ten British runners listed in the Athletics Weekly results were:

7th – Joyce Smith – 2:41:22

10th – Gillian Adams – 2:42:14

12th – Carol Gould – 2:43:50

33rd – Gillian Burley – 2:59:50

42nd – A King – 3:04:44

48th – Rosemary Wright – 3:08:15

53rd – Leslie Watson – 3:11:15

54th – J Pearson – 3:12:17

57th – Frances Mudway – 3:14:57

59th – Jean Lochhead – 3:17:28

A further eleven British women appeared in the top 104 places.

Smith, Adams and Gould took the first three WAAA Championship places. Leslie Watson took first place in the Championship the following year, when Rugby was chosen as the nominated event. March 1981 saw the inaugural London Marathon as we know it today. The official programme for the event lists the top 30 UK women’s marathon times in 1980 with the 14 fastest running under 3 hours. I imagine that many of these women competed in the Avon marathon.

“This race was the deal maker” – the women’s marathon in the Olympics

By the time of the Avon International Women’s Marathon in London, a campaign for the inclusion of the women’s marathon in the Olympics had been going on for several years. The marathon grew in popularity as a racing distance in the 1970s in both the US and the UK, with the birth of mass participation events, such as the New York Marathon which started in 1970. New York, unlike most other marathons, included women as competitors from the start. The Boston Marathon, one of the oldest marathons in the world, finally admitted women runners in 1972 after a campaign by Bobbi Gibb, Kathrine Switzer and many other women who wanted the right to compete at the distance.

This growing public interest in the marathon coincided with the women’s liberation movement. To many people it started to seem ridiculous to limit the distance women could run in competition to just 1.5 miles, because of fears about the effect of the exertion on women’s health.

The International Runners Committee

There were two main initiatives involved in bringing about the inclusion of the women’s marathon in the Olympics. In 1979 two-times marathon world record-holder Jacqueline Hansen formed the International Runners Committee with other runners from around the world. The committee was supported by Nike, a fledgling shoe brand at the time. Their aim was to lobby the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) and International Olympics Committee (IOC) for the inclusion of women’s long-distance races in international competition. They made the case for the 3,000 metres, 5,000 metres and 10,000 metre track races as well as the marathon. None of these distances were included in the Olympics at that time.

The Avon International Running Circuit

The second initiative was Switzer’s work setting up the Avon International Running Circuit. For a new women’s event to be included in the Olympics, the IOC’s rules stated that it had to be widely practised in at least 25 countries and on at least two continents. Switzer’s aim was to provide the evidence that this was the case by staging races in many different countries, and by providing a route for women runners to compete in an international marathon event.

The timing of Avon’s London race was particularly significant because, when the IOC had met in July, they had decided to postpone their decision about the inclusion of the women’s marathon in the 1984 Olympics to their board meeting in February 1981. That meeting would be the last chance to secure its inclusion. The London event exceeded the IOC’s requirements for considering new events, with runners from 27 countries and 5 continents. It was the first time that five women had finished below the 2:40 barrier in a race. And it attracted TV coverage from the BBC and American broadcaster NBC, proving that the public were interested in watching women’s running. Switzer writes:

“Women’s marathon running was an established global sport. London was the proof.”

In February 1981 the IOC voted in favour of adding the women’s marathon and the 3,000 metres to the programme for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. Switzer describes the impact of the decision:

“[Women] now had a destination, not just a dream. Opportunity had made it happen, and opportunity would get them to the starting line in L.A.”

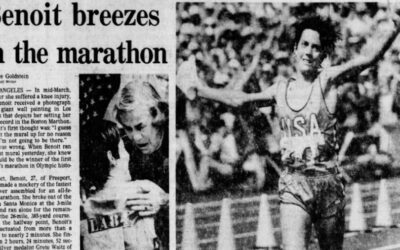

Joan Benoit won the first women’s Olympic marathon, in the third fastest time ever run by a woman. The International Runners Committee continued to campaign for the inclusion of the other distances. The 10,000 metres was run for the first time in Seoul in 1988 and the 5,000 metres replaced the 3,000 metres in Atlanta in 1996.

……………………………………………………………..

I would love to hear from anyone with more information about this race. Do you know who the other British competitors were, or which other countries were represented? Were you there on the day?

……………………………………………………………..

Read my articles about Kathrine Switzer, Joyce Smith and Jacqueline Hansen.

Sources for this article:

The main source for this article is Marathon Woman by Kathrine Switzer, Da Capo Press, 2009.

The main source for this article is Marathon Woman by Kathrine Switzer, Da Capo Press, 2009.

“The fight to establish the women’s race“, chapter from The Olympic Marathon, by Charles C. Lovett, 1997. Reproduced on marathonguide.com.

Details of the Women’s Amateur Athletic Association Marathon Championships, from the NUTS (National Union of Track Statisticians) website.

“Avon calling as 200 runners join women-only marathon“, article by John Cunningham from The Guardian Archive, http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2013/aug/01/women-only-marathon-avon

Partial results of the Avon London International Women’s Marathon, Association of Road Racing Statisticians, more.arrs.net/race/16007

There used to be an archive of website information relating to the Avon International Running Circuit, on the coolrunning.com website. Unfortunately this website was closed down in 2020.

The official programme from the 1981 London Marathon.

Photographs

The Westminster Bridge photograph is by Arthur Klonsky.

The banner photograph shows the start of the London race and was kindly supplied by Kathrine Switzer. Joyce Smith is visible wearing number 1 and Lorraine Moller wearing number 7.

The photograph of Joyce Smith was purchased from Alamy.

I love that book, Katie. Great piece. I wrote a piece for Women’s Running in which I interviewed a woman who ran the first London marathon (not the Avon one). It’s astonishing that women were not allowed to run more than 10k until the 1970s because of bogus fears about their wombs dropping out. The head of the IOC’s most inflammatory quote around the 1960s was that women had no place inside the Olympic Stadium, unless they were there to crown the winning men with their laurels….

Thank you Ronnie. There is so much of interest in Kathrine Switzer’s book, that I decided to focus on that race and see how much I could find out about it. Women in the UK today have so many opportunities to run that we could easily take it for granted, and I think that remembering the struggle to get here is really important. I’m also interested in finding out more about women’s experiences of athletics and sport, growing up in a time when women’s participation was either very limited or not allowed.